64 KiB

The Proto-Ñyqy People

Foreword

Redistribution or sale of this document is strictly prohibited. This document is protected by French law on copyright and is completely owned by its author1 (myself, Lucien “Phundrak” Cartier-Tilet). This document is released for free in various formats on the author’s website2 and is released under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence3.

If you got this document by any other mean than a website on the

.phundrak.com domain, please report it as soon as possible. There is

currently no agreement with the author to redistribute it by any mean

possible. If you wish to redistribute it, please contact the author.

This document is about a constructed language (conlang) I created. However, it will be written as an in-universe document would be. Therefore, any reference to other works, documents or people will be completely fictional. If there is somewhere written that there “needs to be more research done on the subject” or any similar kind of expression, this simply means I haven’t written anything on this subject, and I may not plan to. As you might notice, the style of writing in this document will be inspired mainly by the book Indo-European Language and Culture by Benjamin W. Forston. Go read this book if you haven’t already, it’s extremely interesting (except for the part with the Old Irish and Vedic people and what their kings and queens did with horses, I wish to unread that).

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to persons living or dead, to any real event, or any real people is purely coincidental.

Introduction

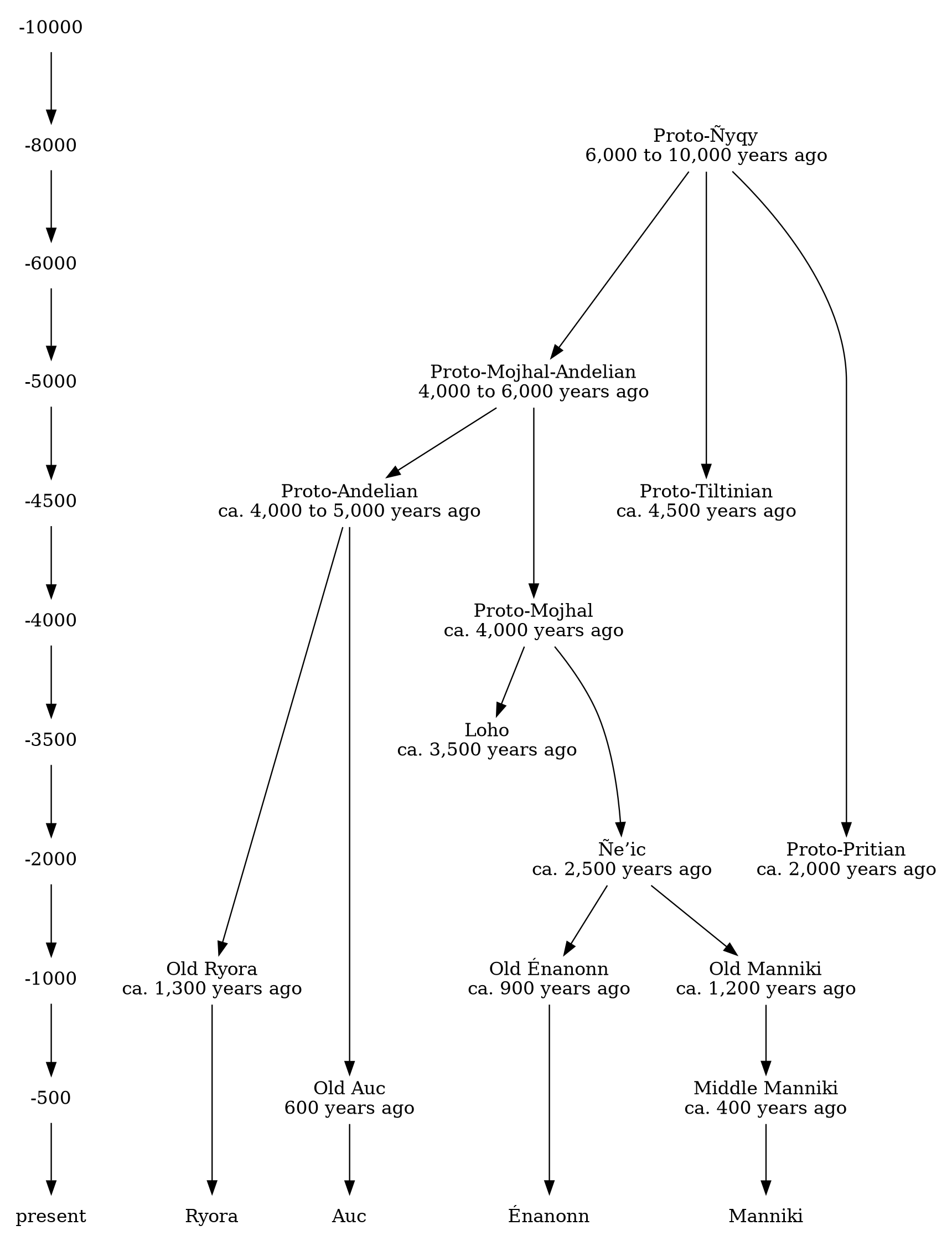

Language Evolution

We are not sure which was the first language ever spoken in our world. Was there even one primordial language, or were there several that spontaneously appeared around our world here and there? We cannot know for certain, this is too far back in our history. Some scientists estimate the firsts of our kind to be gifted the ability to speak lived some hundred of thousand of years back, maybe twice this period even. There is absolutely no way to know what happened at that time with non-physical activities, and we can only guess. We can better guess how they lived, and how they died, than how they interacted with each other, what was their social interaction like, and what were the first words ever spoken on our planet. Maybe they began as grunts of different pitches, with hand gestures, then two vowels became distinct, a couple of consonants, and the first languages sprung from that. This, we do not know, and this is not the subject of this book anyways.

What we do know is, languages evolve as time passes. One language can morph in the way it is pronounced, in the way some words are used, in the way they are shaped by their position and role in the sentence, by how they are organized with each other. A language spoken two centuries back will sound like its decendent today, but with a noticeable difference. Jumping a couple of centuries back, and we lost some intelligibility, and some sentences sound alien to us. A millenium back, and while the language resonates, we cannot understand it anymore. Going the other way around, travelling to the future, would have the same effect, except that we would not necessarily follow only one language, but several, for in different places, different changes would take place. As time goes by, these differences become more and more proeminent, and what was once the same langage becomes several dialects that become less and less similar to one another, until we end up with several languages, sister between themselves, daughters to the initial language.

Relating Languages Between Themselves

We are not sure who first emited the theory of language evolution; this has been lost to time during the great collapse two thousand years back, and only a fraction of the knowledge from back then survived the flow of time. We’re lucky even to know about this. It’s the Professor Loqbrekh who, in 3489, first deciphered some books that were found two decades prior, written in Énanonn. They described the principle of language evolution, and how language families could be reconstructed, how we could know languages are related, and a hint on how mother languages we do not know could be reconstructed. The principle on how historical linguistics are the following:

If two languages share a great number of coincidentally similar features, especially in their grammar, so much so that it cannot be explained by chance only, then these two languages are surely related.

By this process, we can recreate family trees of languages. Some are more closely related to one another than some other, which are more distant. Sometimes, it is even unsure if a language is related to a language tree; maybe the language simply borrowed a good amount of vocabulary from another language that we either now of, or died since.

The best attested languages are the ones we have written record of. In a sense, we are lucky: while we do know a vast majority of the written documents prior to the great collapse were lost during this sad event, we still have a good amount of them left in various languages we can analyze, and we still find some that were lost before then and found back again. The earliest written record we ever found was from the Loho language, the oldest member of the Mojhal language tree attested; the Mojhal tree has been itself linked to the Ñyqy tree some fifty years ago by the Pr Khorlan (3598).

Principles of Historical Linguistics

So, how does historical linguistics work? How does one know what the mother language of a bunch of other languages is? In historical linguistics, we study the similarities between languages and their features. If a feature is obviously common, there is a good chance it is inherited from a common ancestor. The same goes for words, we generally take the average of several words, we estimate what their ancestor word was like, and we estimate what sound change made these words evolve the way they did. If this sound change consistently works almost always, we know we hit right: sound changes are very regular, and exceptions are very rare. And this is how we can reconstruct a mother language that was lost to time thanks to its existing daughter languages.

But as we go back in time, it becomes harder and harder to get reliable data. Through evolution, some information is lost — maybe there once was an inflectional system that was lost in all daughter languages, and reconstructing that is nigh impossible. And since no reconstruction can be attested, we need a way to distinguish these from attested forms of words. This is why attested words are simply written like “this”, while reconstructed words are written with a preceding star like “”. Sometimes, to distinguish both from the text, you will see the word of interest be written either in bold or italics. This bears no difference in meaning.

On Proto-Languages

As we go back in time, there is a point at which we have to stop: we no longer find any related language to our current family, or we can’t find enough evidence that one of them is part of the family and if they are related, they are very distantly related. This language we cannot go beyond is called a proto-language, and it is the mother language of the current language family tree. In our case, the Proto-Ñyqy language, spoken by the Ñyqy people, is the mother language of the Ñyqy language family tree and the ancestor of the more widely known Mojhal languages.

There is something I want to insist on very clearly: a proto-language is not a “prototype” language as we might think at first — it is not an imperfect, inferior language that still needs some iterations before becoming a full-fledged language. It has been proven multiple times multiple times around the world, despite the best efforts of the researchers of a certain empire, that all languages are equally complex regardless of ethnicity, education, time, and place. Languages that are often described as “primitive” are either called so as a way to indicate they are ancient, and therefore close to a proto-language, or they are described so by people trying to belittle people based on incorrect belief that some ethnicities are somehow greater or better than others. This as well has been proven multiple times that this is not true. A proto-language bore as much complexity as any of the languages currently spoken around the world, and a primitive language in linguistic terms is a language close in time to these proto-languages, such as the Proto-Mojhal language (which is also in turn the proto-language of the Mojhal tree). The only reason these languages might seem simpler is because we do not know them and cannot know them in their entierty, so of course some features are missing from it, but they were surely there.

Note that “Proto-Ñyqy” is the usual and most widely accepted spelling of the name of the language and culture, but other spellings are accepted such as “Proto Ñy Qy”, “Proto Ñy Ħy”, “Proto Ḿy Qy”, or “Proto Ḿy Ħy”, each with their equivalent with one word only after the “Proto” part. As we’ll see below in §#Structural-Preview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Consonants-xethtyt058j0, the actual pronunciation of consonants is extremely uncertain, and each one of these orthographies are based on one of the possible pronunciations of the term . In this book, we’ll use the so called “coronal-only” orthography, unless mentionned otherwise. Some people also have the very bad habit of dubbing this language and culture as simply “Ñyqy” (or one of its variants), but this is very wrong, as the term “Ñyqy” designates the whole familiy of languages and cultures that come from the Proto-Ñyqy people. The Tiltinian languages are as much Tiltinian as they are Ñyqy languages, but that does not mean they are the same as the Proto-Ñyqy language, even if they are relatively close in terms of time. When speaking about something that is “Ñyqy”, we are generally speaking about daughter languages and cultures and not about the Proto-Ñyqy language and culture itself.

Note also we usually write this language with groups of morphemes, such as a noun group, as one word like we do with . However, when needed we might separate the morphemes by a dash, such as in .

Reconstructing the Culture Associated to the Language

While the comparative method described in §#Introduction-Principles-of-historical-linguistics-woq10x50e5j0 work on languages, we also have good reasons to believe they also work of culture: if elements of different cultures that share a language from the same family also share similar cultural elements, we have good reasons to believe these elements were inherited from an earlier stage of a common culture. This is an entire field of research in its own right, of course, but linguistics also come in handy when trying to figure out the culture of the Ñyqy people: the presence of certain words can indicate the presence of what they meant, while the impossibility of recreating a word at this stage of the language might indicate it only appeared in later stages of its evolution, and it only influenced parts of the decendents of the culture and language. For instance, the lack of word for “honey” in Proto-Ñyqy but the ability to reconstruct a separate word for both the northern and southern branches strongly suggests both branches discovered honey only after the Proto-Ñyqy language split up into different languages, and its people in different groups, while the easy reconstruction of signifying monkey strongly suggests both branches knew about this animal well before these two groups split up. More on the culture in §#Culture-of-the-Proto-Ñyqy-People-keflq2i0g5j0 below.

Culture of the Proto-Ñyqy People

While the Proto-Ñyqy is the most well attested cultural and linguistic family, the temporal distance between the Proto-Ñyqy people and us makes it extremely hard to reconstruct anything. The various branches of the Ñyqy family evolved over the past eight to twelve past millenia, and some changed pretty drastically compared to their ancestors. Therefore, do not expect an in-depth description of what their society was like, but rather what could be considered an overview compared to some other culture descriptions.

The Name of the Language

First, it is important to know where the name of this language came from. Since it has such a wide spread in this world, giving it a name based on where its daughter branches went would give it a very long name, or with a shorter one we would have very boring or limited names — the “Proto-Northern-Southern” language doesn’t sound very good, and the “Proto-Mojhal-Andelian” language leaves other major branches out, such as the Pritian branch which we cannot ommit, just as the Mojhal and Andelian branches. So, researchers went with the reconstructed word for the inclusive we: . It itself is a coumpound word made up of , which is the first person pronoun, and which is sometimes used as a grammatical morpheme indicating a plural — it also means six, as we will later on, the number system of the Proto-Ñyqy people was a bit complex.

Geographical Location

It is often very hard to find the location of very old reconstructed languages, such as the Proto-Mojhal language itself which location is still not clearly known despite its name. But when it comes to the Proto-Ñyqy people, we have a surprisingly good idea of where they were: in the hot rainforests of the northern main continent, most probably near nowadays’ Rhesodia. We know this thanks to some of their reconstructed words which are typical for the other people that lived or still live in hot rainforests, and these terms are older than the split between the northern and southern groups. For instance, both groups have a common ancestor word for bongo, , as well as for the bonobo, , which are only found in these rainforests.

Society

The Proto-Ñyqy was a matriachal society, led most likely by older women who had an important spiritual role. This cultural trait is found in numerous daughter branches of the Ñyqy family, and it would be unreasonable to think a large amount of them would change in the same way despite many branches being most likely disconnected from one another, and the patriarchal branches almost all retained women as their spiritual figurehead, even if political power passed in the hands of men.

Religion and Beliefs

This question might be the hardest of all to answer, as we can only speculate based on the religions the daughter cultures of the Ñyqy family had, as well as the few hints we can get through the Proto-Ñyqy vocabulary. Through this keyhole, dusted by millenia of cultural and linguistic changes, we can offer an initial answer. It seems the Proto-Ñyqy reveered several gods, with however one god or goddes above them called , that might have been to them some form of queen or some sort of god for the gods themselves. We can find for instance this figure in the Mojhal patheon under the name of Kísce. Other than the parental figure of this divinity, their role is vastly unknown.

Structural Overview

Typological Outline of Proto-Ñyqy

Proto-Ñyqy is a language that appears to be strongly analytical and isolating. It relies mainly on its syntax when it comes to its grammar and seldom on morphological rules if at all. Most of its words contain either one or two syllables and its sentenses often revolve around linked morphemes which could be interpreted as grammatical particules. You can find some examples of Proto-Ñyqy and its translation below as well as its glossing.

-

yq ñe pom qy dem.prox3 home GEN 1sg(ABS) This house is mine

-

cø ñe 1sg.POSS.INCL house(ABS) This is my house

-

pim bú qi coq op mango 2sg(ERG) DU eat PST We (two) ate a mango

-

cø pim i bœ mygú coq ug mún op POSS.1sg mango undef.art(ABS) def.art monkey(ERG) eat SUBJ PROG PST zø qy zúmu op 3sg(ABS) 1sg(ERG) see PST I saw the monkey that would have been eating a mango of mine

In the first and second examples, we can notice the absence of a verb “to be” or any equivalent, this shows existential predicates did not need a verb in order to express the existance of something and its attributes. This also reveals the word order of the genitive form in Proto-Ñyqy, the genitive particle follows the element it propertizes and is followed by its property. For instance, in , is the first person singular). I characterize this house, therefore this house is of me, this is my house. The main difference between the first and the second examples is the first example is the accent in the first example is on the fact that said house is mine, whereas in the second example “my house” is simply presented to the interlocutor.

As you can see in the third example, Proto-Ñyqy used to have a dual number which has been lost in most of its decendent languages, and the remaining languages employ the former dual as their current plural dissmissing instead the old plural. As indicated by its name, the dual was used when referencing to two elements when an otherwise greater amount of elements would have required the plural. Hence, in this example, you could consider to be kind of a 2DU pronoun.

Finally, the fourth example gives us an overview of Proto-Ñyqy syntax, such as a different position depending on whether we use an indefinite or definite article, as well as a subclause inserted in the main clause defining a noun phrase, here . We can also clearly see the word order of main clauses presented as Absolutive-Ergative-Verb, Proto-Ñyqy being most likely a mostly ergative language.

It is to be noted that although it is supposed Proto-Ñyqy was a mostly analytical language, some people like to write related morphemes together as one word, hyphenated or not. Thus, the third example could also be written as by some. It is due to the fact Proto-Ñyqy was for a long time thought to be an agglutinative language and the habit of writing related morphemes as one word stuck around. However, nowadays we know an analytical Proto-Ñyqy is instead most likely and scolars began writing morphenes separated from each other instead.

Phonetic Inventory and Translitteration

Vowels

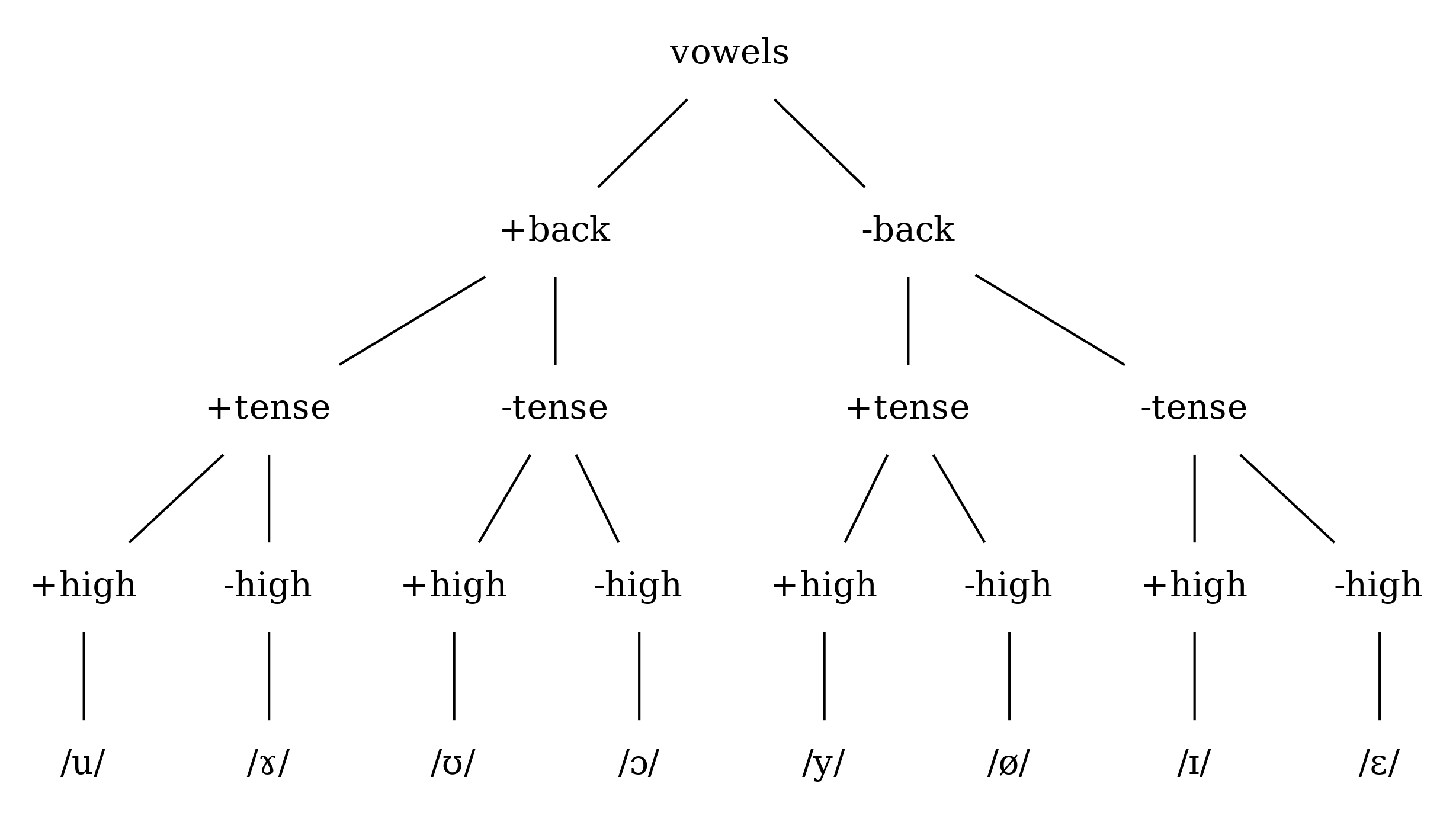

As we stand today, eight vowels were reconstructed for Proto-Ñyqy, as presented in the table table:vowels:trans. Below is a short guide to their pronunciation:

- e

- as in General American English “bed” [bɛd]

- i

- as in General American English “bit” [bɪt]

- o

- as in General American English “thought” [θɔːt]

- ø

- as in French “peu” [pø]

- œ

- as in Scottish Gaelic “doirbh” [d̪̊ɤrʲɤv]

- u

- as in General American English “hook” [hʊ̞k]

- ú

- as in General American English “boot” [bu̟ːt]

- y

- as in French “dune” [d̪yn]

| / | < | < |

|---|---|---|

| antérieures | postérieures | |

| fermées | y | ú |

| pré-fermées | i | u |

| mi-fermées | ø | œ |

| mi-ouvertes | e | o |

We also have a ninth vowel, noted <ə> which denotes an unknown vowel. It is most likely this was before the Proto-Ñyqy breakup a simple schwa standing where a vowel got reduced either at an earlier stage than Proto-Ñyqy or during the breakup of the language. Depending on the languages that evolved from Proto-Ñyqy, some got rid of it later while some other reinstated it as a full vowel with different rules each on which vowel it would become. Thus in the current stage of reasearch on Proto-Ñyqy, we cannot know for certain which vowel it should have been.

It is however possible to create a featural tree for the known vowels, determining which would have been considered closer to others, as seens with figure tree:vowels.

(conlanging-list-to-graphviz vowels)graph{graph[dpi=300,bgcolor="transparent"];node[shape=plaintext];"vowels-0jae0mb5jxtn"[label="vowels"];"+back-0jae0mb5jxtx"[label="+back"];"vowels-0jae0mb5jxtn"--"+back-0jae0mb5jxtx";"+tense-0jae0mb5jxu1"[label="+tense"];"+back-0jae0mb5jxtx"--"+tense-0jae0mb5jxu1";"+high-0jae0mb5jxu4"[label="+high"];"+tense-0jae0mb5jxu1"--"+high-0jae0mb5jxu4";"/u/-0jae0mb5jxu6"[label="/u/"];"+high-0jae0mb5jxu4"--"/u/-0jae0mb5jxu6";"-high-0jae0mb5jxub"[label="-high"];"+tense-0jae0mb5jxu1"--"-high-0jae0mb5jxub";"/ɤ/-0jae0mb5jxue"[label="/ɤ/"];"-high-0jae0mb5jxub"--"/ɤ/-0jae0mb5jxue";"-tense-0jae0mb5jxuq"[label="-tense"];"+back-0jae0mb5jxtx"--"-tense-0jae0mb5jxuq";"+high-0jae0mb5jxus"[label="+high"];"-tense-0jae0mb5jxuq"--"+high-0jae0mb5jxus";"/ʊ/-0jae0mb5jxuv"[label="/ʊ/"];"+high-0jae0mb5jxus"--"/ʊ/-0jae0mb5jxuv";"-high-0jae0mb5jxv1"[label="-high"];"-tense-0jae0mb5jxuq"--"-high-0jae0mb5jxv1";"/ɔ/-0jae0mb5jxv3"[label="/ɔ/"];"-high-0jae0mb5jxv1"--"/ɔ/-0jae0mb5jxv3";"-back-0jae0mb5jxvp"[label="-back"];"vowels-0jae0mb5jxtn"--"-back-0jae0mb5jxvp";"+tense-0jae0mb5jxvs"[label="+tense"];"-back-0jae0mb5jxvp"--"+tense-0jae0mb5jxvs";"+high-0jae0mb5jxvv"[label="+high"];"+tense-0jae0mb5jxvs"--"+high-0jae0mb5jxvv";"/y/-0jae0mb5jxvy"[label="/y/"];"+high-0jae0mb5jxvv"--"/y/-0jae0mb5jxvy";"-high-0jae0mb5jxw4"[label="-high"];"+tense-0jae0mb5jxvs"--"-high-0jae0mb5jxw4";"/ø/-0jae0mb5jxw7"[label="/ø/"];"-high-0jae0mb5jxw4"--"/ø/-0jae0mb5jxw7";"-tense-0jae0mb5jxwi"[label="-tense"];"-back-0jae0mb5jxvp"--"-tense-0jae0mb5jxwi";"+high-0jae0mb5jxwl"[label="+high"];"-tense-0jae0mb5jxwi"--"+high-0jae0mb5jxwl";"/ɪ/-0jae0mb5jxwo"[label="/ɪ/"];"+high-0jae0mb5jxwl"--"/ɪ/-0jae0mb5jxwo";"-high-0jae0mb5jxwt"[label="-high"];"-tense-0jae0mb5jxwi"--"-high-0jae0mb5jxwt";"/ɛ/-0jae0mb5jxww"[label="/ɛ/"];"-high-0jae0mb5jxwt"--"/ɛ/-0jae0mb5jxww";}

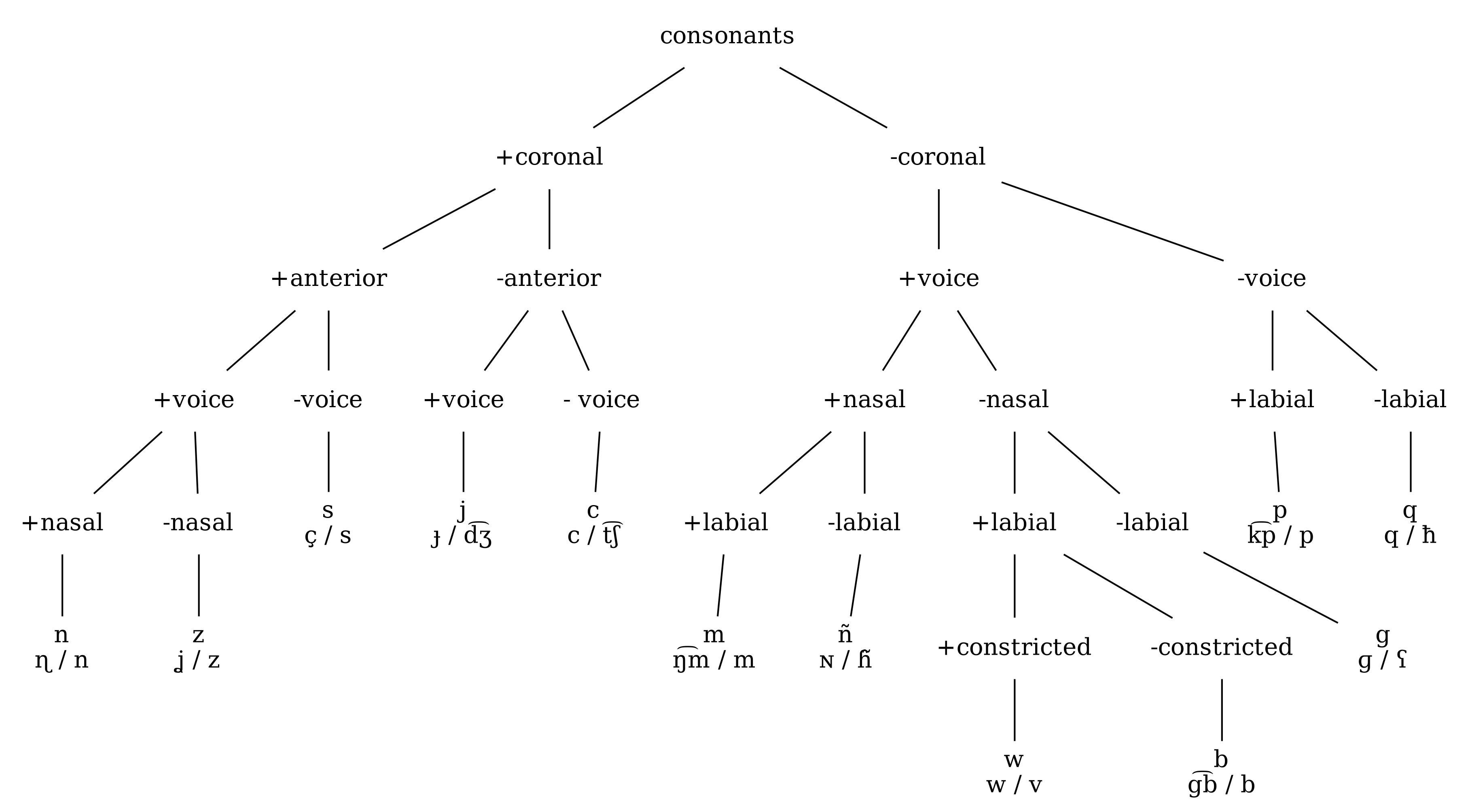

Consonants

The topic of consonants, unlike vowels, is a hot debate among linguists. while we are pretty sure proto-ñyqy has twelve consonants, we are still unsure which consonants they are due to the extreme unstability of the dorsal feature, and there is seemingly no consistency as to how the consonants stabilized in the different languages that emerged from the proto-ñyqy breakup. it is only in the recent years Ishy Maeln proposed a new theory that is gaining traction among proto-ñyqy specialists: each consonant could be pronounced either as a dorsal or as a non-dorsal depending on its environment and both potential pronunciation can be correct. she even goes further and proposes proto-ñyqy had an alternating rule stating a given consonant had to be non-dorsal if the previous one was, and vice versa. this would explain the common pattern of dorsal consonants alternation found in some early languages found after the breakup such as proto-mojhal. this phenomenon is more thouroughly explained in §#Structural-Preview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Consonants-xethtyt058j0.

You can find the featural tree of the Proto-Ñyqy consonants in the figure tree:cons. Each grapheme displays below its dorsal pronunciation on the left and its non-dorsal pronunciation on the right.

(conlanging-list-to-graphviz consonants)graph{graph[dpi=300,bgcolor="transparent"];node[shape=plaintext];"consonants-0jae0mrv0dgn"[label="consonants"];"+coronal-0jae0mrv0dgx"[label="+coronal"];"consonants-0jae0mrv0dgn"--"+coronal-0jae0mrv0dgx";"+anterior-0jae0mrv0dh1"[label="+anterior"];"+coronal-0jae0mrv0dgx"--"+anterior-0jae0mrv0dh1";"+voice-0jae0mrv0dh3"[label="+voice"];"+anterior-0jae0mrv0dh1"--"+voice-0jae0mrv0dh3";"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dh6"[label="+nasal"];"+voice-0jae0mrv0dh3"--"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dh6";"n\nɳ / n-0jae0mrv0dh9"[label="n\nɳ / n"];"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dh6"--"n\nɳ / n-0jae0mrv0dh9";"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dhf"[label="-nasal"];"+voice-0jae0mrv0dh3"--"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dhf";"z\nʝ / z-0jae0mrv0dhi"[label="z\nʝ / z"];"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dhf"--"z\nʝ / z-0jae0mrv0dhi";"-voice-0jae0mrv0dht"[label="-voice"];"+anterior-0jae0mrv0dh1"--"-voice-0jae0mrv0dht";"s\nç / s-0jae0mrv0dhw"[label="s\nç / s"];"-voice-0jae0mrv0dht"--"s\nç / s-0jae0mrv0dhw";"-anterior-0jae0mrv0did"[label="-anterior"];"+coronal-0jae0mrv0dgx"--"-anterior-0jae0mrv0did";"+voice-0jae0mrv0dif"[label="+voice"];"-anterior-0jae0mrv0did"--"+voice-0jae0mrv0dif";"j\nɟ / d͡ʒ-0jae0mrv0dii"[label="j\nɟ / d͡ʒ"];"+voice-0jae0mrv0dif"--"j\nɟ / d͡ʒ-0jae0mrv0dii";"- voice-0jae0mrv0dio"[label="- voice"];"-anterior-0jae0mrv0did"--"- voice-0jae0mrv0dio";"c\nc / t͡ʃ-0jae0mrv0dir"[label="c\nc / t͡ʃ"];"- voice-0jae0mrv0dio"--"c\nc / t͡ʃ-0jae0mrv0dir";"-coronal-0jae0mrv0djo"[label="-coronal"];"consonants-0jae0mrv0dgn"--"-coronal-0jae0mrv0djo";"+voice-0jae0mrv0djr"[label="+voice"];"-coronal-0jae0mrv0djo"--"+voice-0jae0mrv0djr";"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dju"[label="+nasal"];"+voice-0jae0mrv0djr"--"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dju";"+labial-0jae0mrv0djw"[label="+labial"];"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dju"--"+labial-0jae0mrv0djw";"m\nŋ͡m / m-0jae0mrv0djz"[label="m\nŋ͡m / m"];"+labial-0jae0mrv0djw"--"m\nŋ͡m / m-0jae0mrv0djz";"-labial-0jae0mrv0dk5"[label="-labial"];"+nasal-0jae0mrv0dju"--"-labial-0jae0mrv0dk5";"ñ\nɴ / ɦ̃-0jae0mrv0dk7"[label="ñ\nɴ / ɦ̃"];"-labial-0jae0mrv0dk5"--"ñ\nɴ / ɦ̃-0jae0mrv0dk7";"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dkk"[label="-nasal"];"+voice-0jae0mrv0djr"--"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dkk";"+labial-0jae0mrv0dkn"[label="+labial"];"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dkk"--"+labial-0jae0mrv0dkn";"+constricted-0jae0mrv0dkq"[label="+constricted"];"+labial-0jae0mrv0dkn"--"+constricted-0jae0mrv0dkq";"w\nw / v-0jae0mrv0dkt"[label="w\nw / v"];"+constricted-0jae0mrv0dkq"--"w\nw / v-0jae0mrv0dkt";"-constricted-0jae0mrv0dky"[label="-constricted"];"+labial-0jae0mrv0dkn"--"-constricted-0jae0mrv0dky";"b\ng͡b / b-0jae0mrv0dl1"[label="b\ng͡b / b"];"-constricted-0jae0mrv0dky"--"b\ng͡b / b-0jae0mrv0dl1";"-labial-0jae0mrv0dld"[label="-labial"];"-nasal-0jae0mrv0dkk"--"-labial-0jae0mrv0dld";"g\nɡ / ʕ-0jae0mrv0dlg"[label="g\nɡ / ʕ"];"-labial-0jae0mrv0dld"--"g\nɡ / ʕ-0jae0mrv0dlg";"-voice-0jae0mrv0dmf"[label="-voice"];"-coronal-0jae0mrv0djo"--"-voice-0jae0mrv0dmf";"+labial-0jae0mrv0dmi"[label="+labial"];"-voice-0jae0mrv0dmf"--"+labial-0jae0mrv0dmi";"p\nk͡p / p-0jae0mrv0dml"[label="p\nk͡p / p"];"+labial-0jae0mrv0dmi"--"p\nk͡p / p-0jae0mrv0dml";"-labial-0jae0mrv0dmr"[label="-labial"];"-voice-0jae0mrv0dmf"--"-labial-0jae0mrv0dmr";"q\nq / ħ-0jae0mrv0dmt"[label="q\nq / ħ"];"-labial-0jae0mrv0dmr"--"q\nq / ħ-0jae0mrv0dmt";}#+CAPTION:Feature Tree of Proto-Ñyqy Consonants

As you can see, each one of the consonants have their two alternative indicated below their grapheme. In the case of the coronal consonants, the alternative consonant is obtained by replacing the anterior feature by the dorsal feature when it is present.

The way of writing consonants was therefore standardized as presented in the table table:consonants-pronunciation.

| Main Grapheme | Dorsal Phoneme | Non-Dorsal Phoneme | Alternate Grapheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| ñ | ḿ | ||

| q | ħ, h1 | ||

| g | ȟ, h2 | ||

| c | ł | ||

| j | ʒ | ||

| w | l | ||

| m | r, r1 | ||

| p | xh, r2 | ||

| b | rh, r3 | ||

| n | y | ||

| s | x, r4 | ||

| z | ɣ, r5 |

For each of these consonants, the letter chosen represents what we suppose was the most common or the default pronunciation of the consonant represented. In the table are also included alternate graphemes you might find in other, mostly older works, though they are mostly deprecated now.

As you can see, Proto-Ñyqy had potentially two different consonants that could be pronounced as . Although it did not influence Proto-Ñyqy as far as we know, it definitively influenced the Pritian branch of the family, with <ñ> and <m> influencing differently the vowel following it.

Several consonants used to be unknown at the beginnings of the Proto-Ñyqy study, as can be seen with the old usage of <h1, h2, r1, r2, r3, r4, and r5>. These are found mostly in the earlier documents but progressively dissapear as our understanding of the Proto-Ñyqy grew during the past century. They are not used anymore, but any student that wishes to read older documents on Proto-Ñyqy should be aware of these.

Pitch and Stress

It is definitively known Proto-Ñyqy had a stress system that was used both on a clause and on a word level, as it has been inherited by the languages that evolved from it. However, it is not possible to reconstruct it accurately, we only know the vowel <ə> was unstressed and only appeared in words with two syllables or more. However, we do not know if it had any morphological meaning or if it was productive.

On the other hand, we are much less sure about whether it had an accent system, and if it did whether it was productive or not. Most of the languages that evolved from Proto-Ñyqy had or have one such as the Mojhal-Andelian family, but some don’t such as the Pritian family. The most commonly accepted answer is a pitch system appeared after the breakup of the pitchless branches which happenned earlier than the other branches which do have a pitch system. In reconstructed Proto-Ñyqy however, if such a system was present, pitches were most likely non-phonemic and unproductive. It only gained productivity in later stages, after the first breakups we know, in a common unknown ancestor language of the branches which did or still do have either an accent or a pitch system, and even there the evolutions seem to have happened in different ways depending on the branches. It is therefore impossible to know what the pitch system of Proto-Ñyqy was if it had one.

Phonotactics

Syllable Structure

The prototypical syllable in Proto-Ñyqy appears as a (C)V(C)(C) syllable with at least one consonant around the vowel, either in the onset or in the coda. At most, it can have one consonant in the onset and two in the coda.

No special rule have been found to rule the onset, it can host any consonant without any effect on the vowel.

However, it has been found the coda has some rules:

- two nasal consonants cannot follow each other — no

- two coronal consonants cannot follow each other — no

- labial consonants are never found with another consonant in the coda — no

For instance, would be pronounced as {{{recon(noc gebec)}}}. It is most likely the features to chose from when converting a consonant from a coronal to a non-coronal were considered as absent by default. This results in the table table:coronal-to-non-coronal-consonants — as you can see, the pair <z> and <j> and the pair <s> and <c> convert to the same consonant respectively.

| Coronal Consonant | Non-Coronal Consonant |

|---|---|

| n | ñ |

| z | g |

| s | q |

| j | g |

| c | q |

It has also been found that if two coronal consonants do follow each other in cross-syllabic environments, with the first one in the coda of a first syllable and the second one in the onset of a second syllable, then the former will become voiced as the latter.

Similarly, if two nasal consonants are found near each other in a cross-syllabic environment, the second nasal consonant will become denasalized. Thus, we get the conversion table table:consonants-denasalization.

| Nasal Consonant | Non-Nasal Consonant |

|---|---|

| n | z |

| m | w |

| ñ | b |

It has also been found a schwa tends to appear between syllables when the first one ends with two consonants and the second one begins with one.

Consonantal Dorsal Alternation

As mentioned above in §#Structural-Preview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Consonants-xethtyt058j0, it seems probable according to Maeln’s theory consonants were alternating between dorsals and non-dorsals. We do not know if it only happened between words, within words, or along whole clauses, but this would explain much of the different languages that evolved from Proto-Ñyqy. Table table:word-consonantal-dorsal-alternation shows different possible pronunciation of Proto-Ñyqy words with word-wise consonantal dorsal alternation whether the first consonant is to be considered a dorsal consonant or not. Note the nasal switch as well as the extra schwa insertion in the third example as described above in chapter §#Structural-Overview-Phonotactics-Syllable-Structure-hhx3zk40f8j0.

| Word | Dorsal-Initial | Dorsal-Final |

|---|---|---|

Word Structure

Words in Proto-Ñyqy belong to one of two categories: either a bound morphene, or a free morpheme. The former have a restricted use and must be used in certain contexts and do not mean anything by themselves. In Proto-Ñyqy, they are most of the time grammatical morphemes, for instance for marking the genitive between two words or the tense of a verb. Although the morpheme is bound, it does not mean it is part of another word — it will still be most of the time a full fledged word obeying the phonological rules of a whole word.

On the other hand, free morphemes do not require another morpheme to exist. The most basic example is the sentence which means “It is a house”. It is also the word for “house” by itself. All nouns in Proto-Ñyqy are free morphemes, although they can act as bound morphemes if need be such as when they act as adjectives.

Among multi-syllable world, it is not rare to find compound world made from other known root words. Generally, the order of the new word roughly follows the adjective order, however some words might reflect short noun phrases that became over time a word by itself through abbreviation with for instance (shawl, veil) composed of . This term is most likely the abbreviation of , or head fabric. Phonetic rules on abbreviation in Proto-Ñyqy are unfortunately very much unknown with no consensus reached on this point, most of them might be older innovations.

Dictionary

B

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) tooth/teeth

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) something bad, badness

- (n) mischief, ill-will, maliciousness

- (n) dirtiness

C

-

{{{def}}}

- (pron) my, first person singular possessive pronoun

E

G

I

J

M

N

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) old age

- (n) elderly person

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) youth

- (n) youngster, teenager

Ñ

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) human being

- (n) someone

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) house

O

Ø

Œ

P

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) bonobo

-

{{{def}}}

- genitive particle

Q

-

{{{def}}}

- (pron) first person singular

S

U

Ú

W

Y

-

{{{def}}}

- demonstrative of proximity, designating something visible by but far from both speakers.

Z

-

{{{def}}}

- (n) bongo (antelope)