84 KiB

Eittland

- Foreword

- Eittland

- Structural Overview

- Typological Outline of the Eittlandic Language

- Phonetic Inventory and Translitteration

- Evolution from Early Old Norse to Eittlandic

- hʷ > ʍ

- C / #h_ > C[-voice]

- g / {#,V}_{V,#} > ɣ

- V / _# > ∅ ! j _

- V / j_# > ə

- Vː / _# > ə

- ɣ / {#,V}_ > j

- gl > gʲ

- d g n s t / _j > C[+palat]

- j > jə / _#

- u / V_ > ʊ

- {s,z} / _C[+plos] > ʃ

- f / {V,C[+voice]}_ {V,C[+voice],#} > v

- l / _j > ʎ

- ə[-long] / C_# > ∅

- ɑʊ > oː

- C[+long +plos -voice] > C[+fric] ! / _C > C[+long +plos] > C[-long]

- r > ʁ (Eastern Eittlandic)

- Great Vowel Shift

- V / _N > Ṽ[-tense] ! V[+high] (Southern Eittlandic)

- t / _C > ʔ ! _ʃ

- VU > ə ! diphthongs (Western Eittlandic)

- Vowel Inventory

- Consonant Inventory

- Pitch and Stress

- Regional accents

- Evolution from Early Old Norse to Eittlandic

- Structure of a Nominal Group

- Dictionary

- Table Index

- Footnotes

Foreword

On This Document

Redistribution or sale of this document is strictly prohibited. This document is protected by French law on copyright and is completely owned by its author1 (myself, Lucien “Phundrak” Cartier-Tilet). This document is dual-licensed under the GFDL license2 for the text and the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license3 for the images.

If you got this document by any other mean than a website on the

.phundrak.com domain, please report it as soon as possible. There is

currently no agreement with the author to redistribute it by any mean

possible. If you wish to redistribute it, please contact the author.

This document is about a constructed language (conlang) I created. It will be written as an in-universe document, in an alternate history where the Eittlandic Kingdom actually exists in our world, with its history intertwined with ours. Any vague part about any linguistical or cultural aspect is most likely due to a lack of worldbuilding, so if you read something along the lines of “more research needs to be done on the subject” simply means I have not yet written on it (or I may not plan to).

A Warning to the Reader

This document deals with the evolution of a real historic language towards a completely made up language, as well as the evolution of a similarly made up people in a made up country. I am no linguist, ethnologist, nor historian, and making this requires a lot of knowledge which I don’t have (if anything, you could consider me an armchair linguists: I read lots of books on the subject). Therefore, I will take shortcuts here and there on various topics.

Any “fact” you might learn about the Old Norse people, language, or history might be altered reality if not straight up wrong, although I do try to strive to achieve something believable and as close as I can to reality.

Let me reiterate: I am no expert in the subjects presented here, do not take anything I say at face value. I believe the scientific term for some stuff written here is “bullshit”.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to persons living or dead, to any real event, or any real people is purely coincidental.

List of abbreviations

- adj

- adjective

- adv

- adverb

- f

- strong feminine noun or adjective

- m

- strong masculine noun or adjective

- n

- strong neutral noun or adjective

- N

- noun

- prep

- preposition

- v

- verb

- w

- weak noun or adjective

Eittland

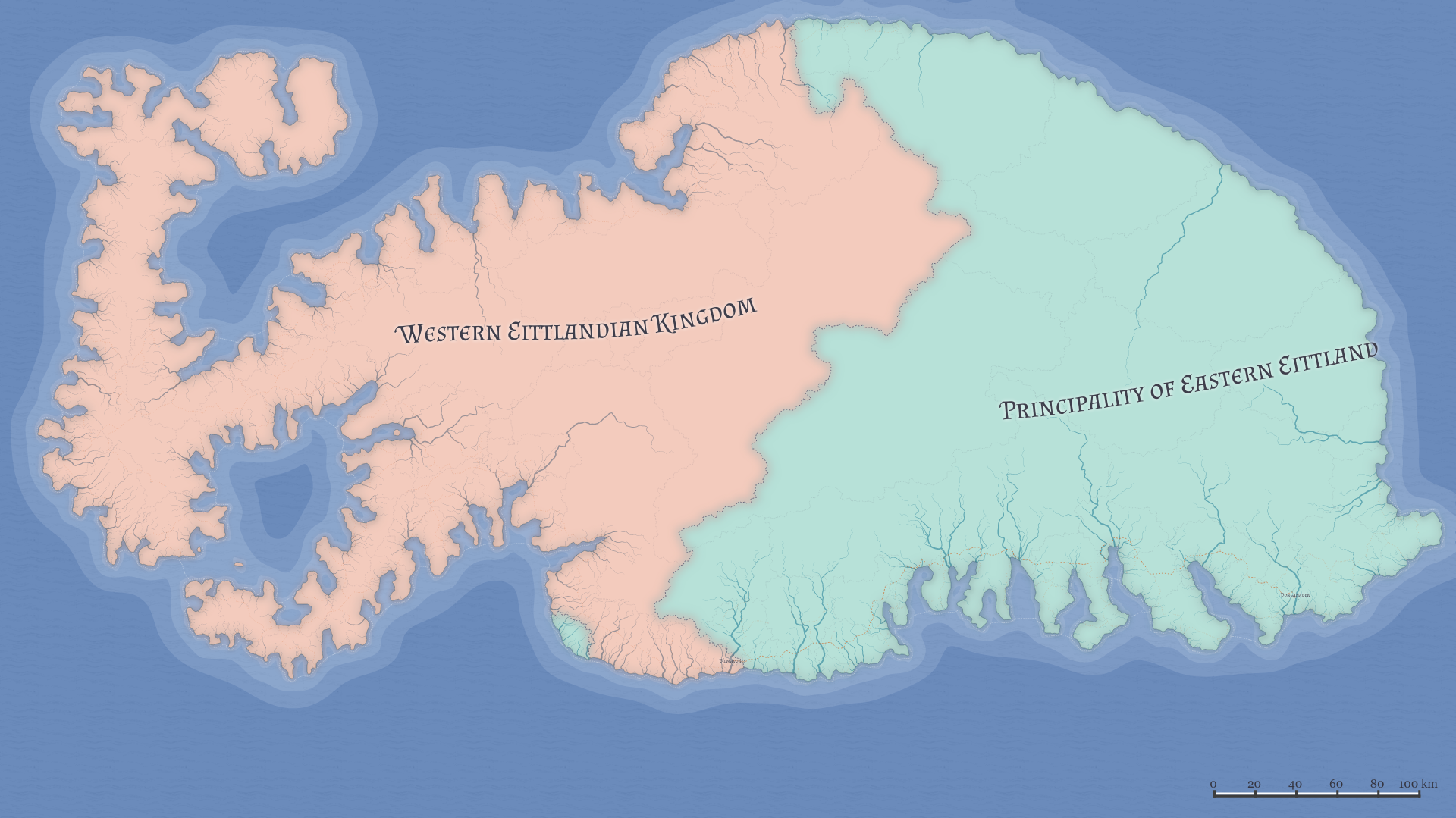

Eittland (Eittlandic: Eittland ) is part of the family of Nordic countries, with a population of 31.5 millions as per the 2019 national census. It has a superficy of 121 km2, making it the second largest island in Europe after Great Britain. Its capital Đeberget is the largest eittlandic city with a population of 1.641.600 in 2019. The island is naturally separated in two, its western and eastern sides, by a chain of volcanoes spawning on the separation of the North American and the Eurasian plates, much like its northern sister Iceland. Thus, its Eastern side covers 49km2 of the island and hosts 11.3 million inhabitants while the western side covers 72km2 with a population of 20.1 millions.

Geography

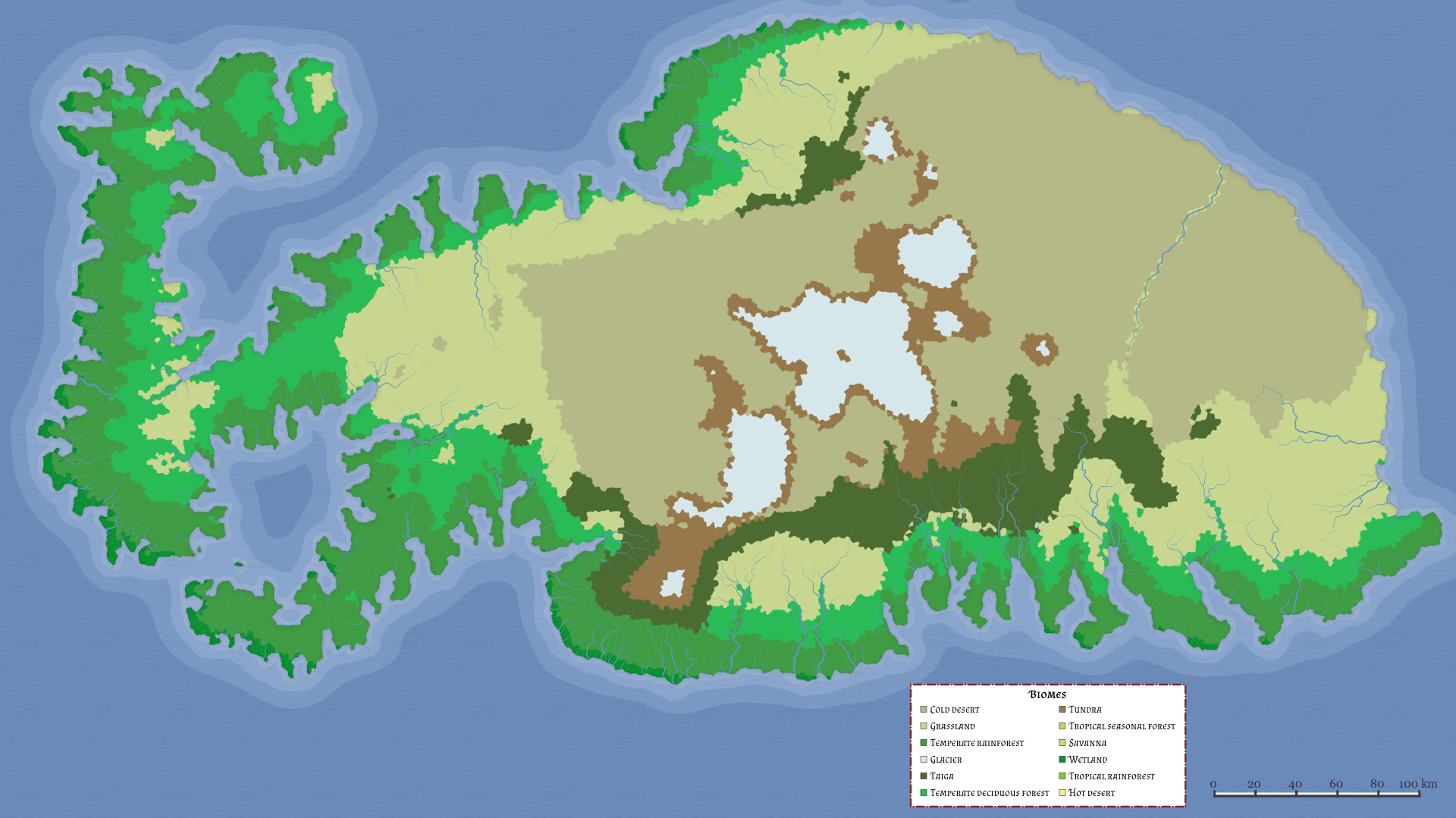

Eittland is an active volcanic island. In its center we can find the most active volcanoes, surrounded by glaciers and some regular mountains. It is surrounded by some taiga, taiga plains covered mainly by ashen pines (pinus fraxinus), and a large cold desert covering most of the center of the island and its northern eastern part. Outside of this largely unpopulated region, Eastern Eittland mainly consists of grasslands with some temperate rainforests on its southern shores as well as some occasional wetland and marshes. On the other hand, Western Eittland has a lot more temperate deciduos forests, temperate rainforests and some more wetlands and marshes still. Three small cold deserts spawn in Western Eittland, including one north east of Đeberget not far from the city. More details can be found in the map img:map-biomes. Overall, the southern and western parts of Eittland can be compared to Scotland in terms of temperatures, or a warmer Iceland.

Eastern Eittland is also recognizable by its great amount of flat shorelines, especially in its northern and eastern parts which are part of the more recent paths of lava flows. On the other hand, its few fjords and the numerous fjords found in the western part of the island are characteristic of much older parts of Eittland. The Fjord themselves were formed during the last ice age, while the smoother shore lines formed since. Western Eittland also has two main bays which are two very old caldeira volcanoes. It is not known whether they will be one day active again or not.

Culture

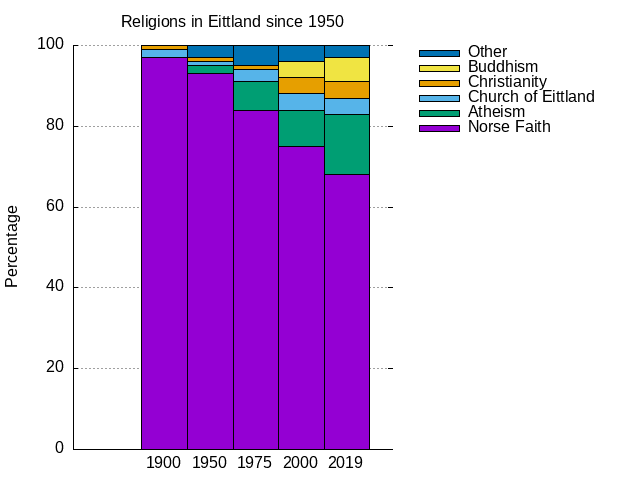

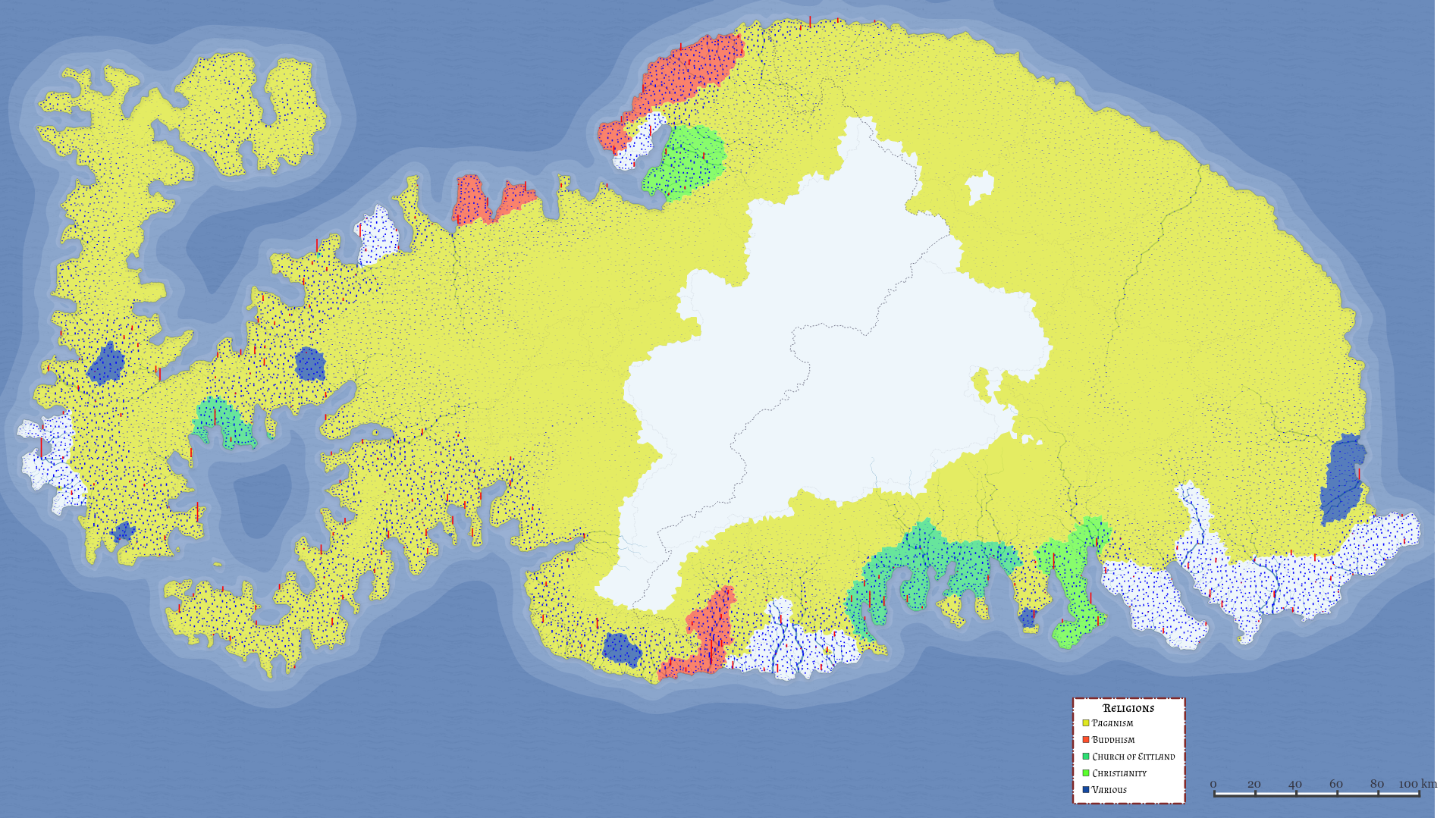

The Eittlandic people share a common basis for their culture which remained rather conservative for much longer than the other nordic people due to its resistance towards Christianity conversion. The number of people adhering to Norse beliefs remained very high through the ages and only recently began declining, going from 93% of Eittlanders declaring themselves follower of the Norse Faith in 1950 to 68% in 2019. This decline is also due to either people converting to a religion or due to the immigration boom from the last seventy years, though the main reason is the decline in people identifying to any faith at all — the number of atheists went from only 2% of Eittlanders in 1940 to 15% in 2019. The evolution of the religious population is shown in the chart chart:religions, and a geographical distribution of these in 2019 can be found in the map map:religion — note that only the main religion is shown in a particular area and religions with less people in said area are not shown. You can also see on said map the population repartition of Eittland.

set title "Religions in Eittland since 1950"

set key invert reverse Left outside

set yrange [0:100]

set grid y

set ylabel "Percentage"

set border 3

set style data histograms

set style histogram rowstacked

set style fill solid border -1

set boxwidth 1

plot data u 2:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Norse Faith', \

data u 3:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Atheism', \

data u 4:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Church of Eittland', \

data u 5:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Christianity', \

data u 6:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Buddhism', \

data u 7:xticlabels(1) axis x1y1 title 'Other'

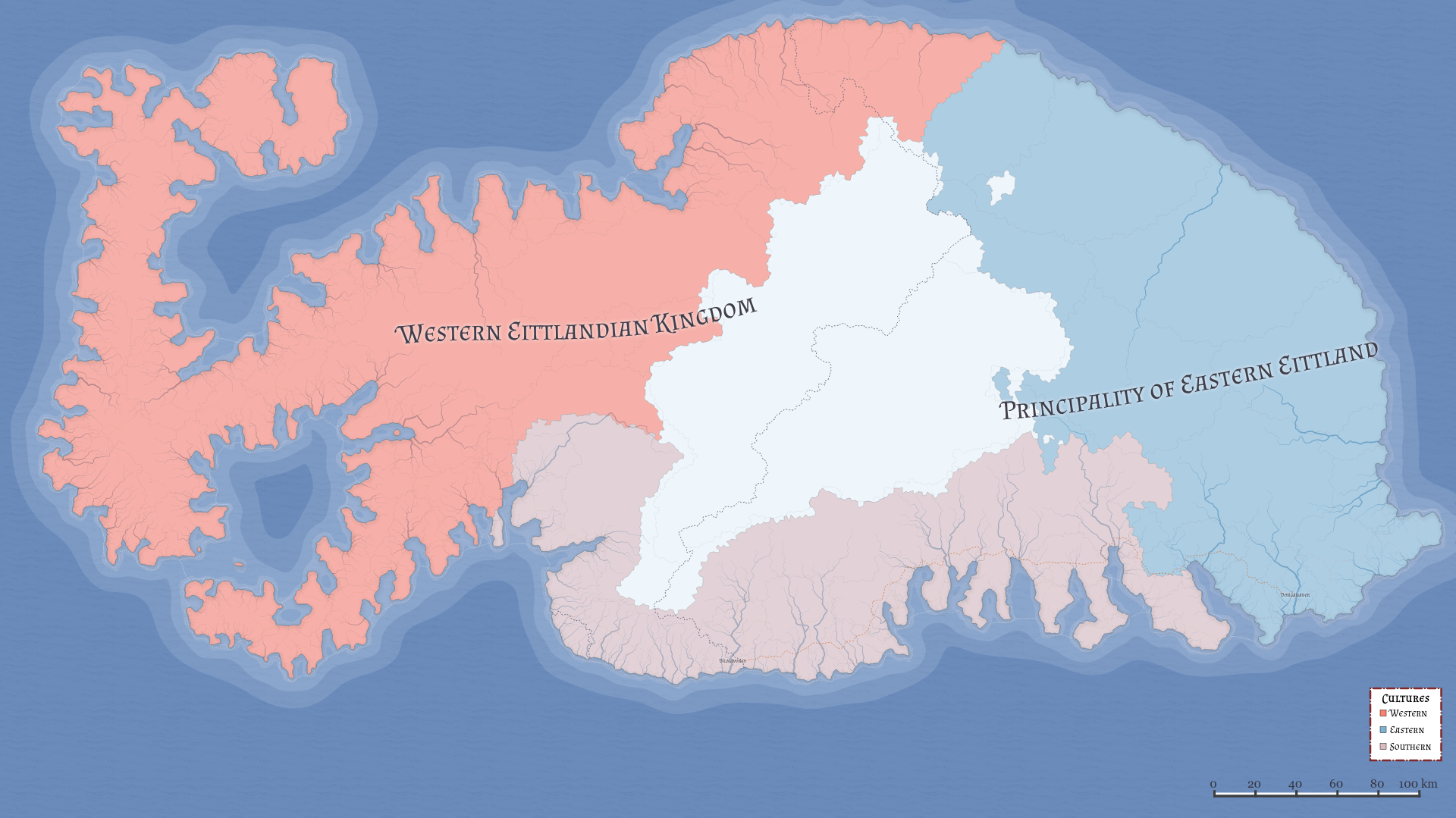

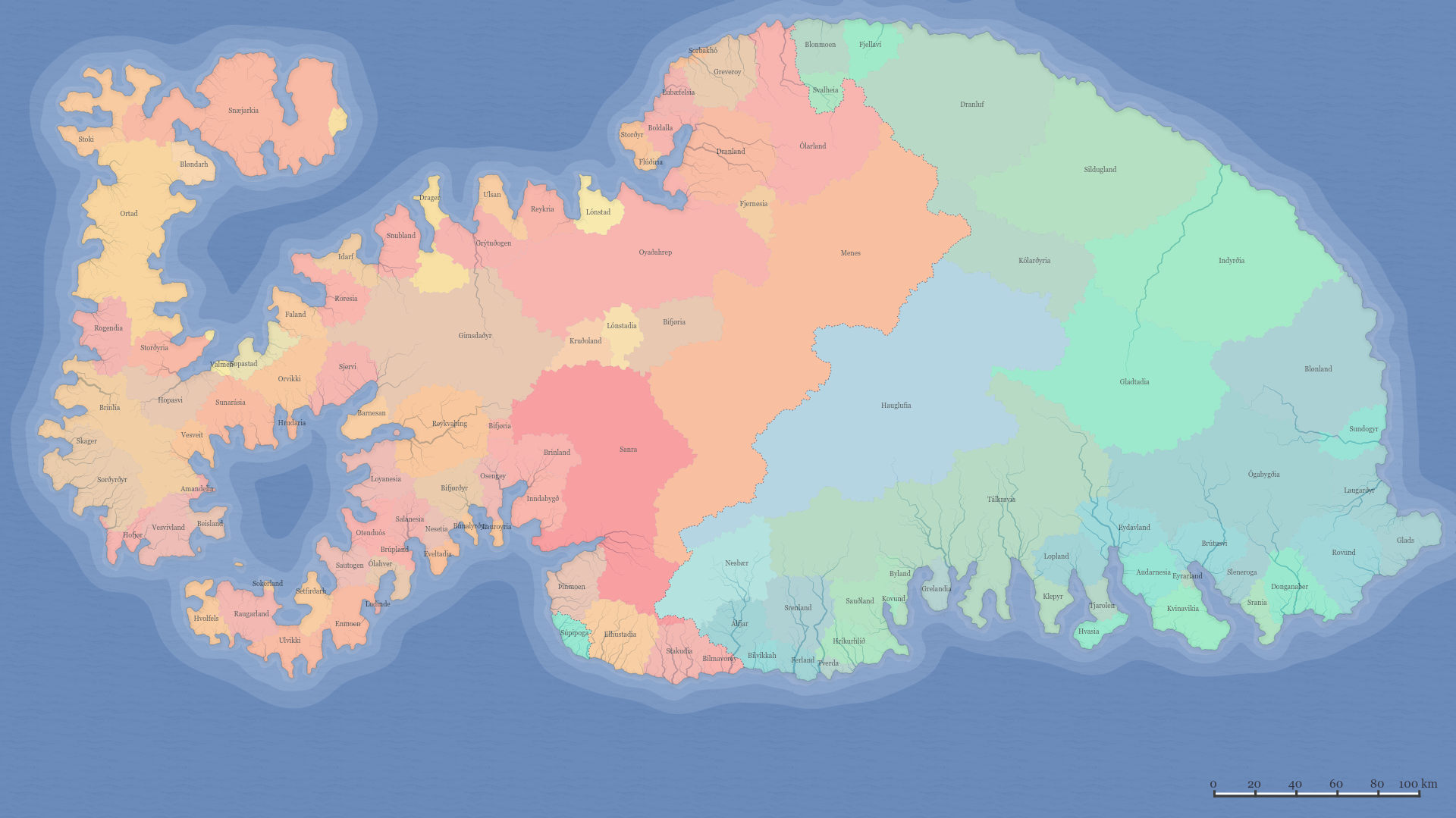

There is also a regional cultural difference between Western, Eastern, and Southern Eittland marked with some differences in traditions and language. There is currently a nationalist movement in Southern Eittland so a new state is created within the Kingdom of Eittland. The repartition of the different eittlandic cultures is shown in the map map:culture.

Standard Eittlandic is a relatively young language, created in the 1960s by the government in order to create a standard dialect to facilitate communications between Eittlanders and make learning the language easier. Standard Eittlandic is now enforced as the de facto legal language of the High Kingdom of Eittland, used by its government, schools, and universities, but the local dialects are still widely spoken privately and in business which remains regional. They still have a strong presence in popular media and are still spoken by younger generations, however, a decline has been registered since the 90s among young people living in cities, speaking more and more in Standard Eittlandic instead. Dialects are also rarely used on the internet outside of private conversation. An estimate of 17% of the Eittlandic population younger than 25 in 2017 do not speak any dialectal Eittlandic outside of Standard Eittlandic, although only 2% of them do not understand their family’s dialectal Eittlandic. Standard Eittlandic also became the default dialect for Eittlandic communities living outside of Eittland — in these communities the inability of speaking other dialects rise to 61% while the ability to understand them rises to 25% among Eittlanders younger than 25 in 2018 and who still have Eittlandic as their mother tongue.

It is estimated only 0.05% of people living in Eittland do not speak any Eittlandic dialect, all of them being immigrants or children of immigrants. It is therefore safe to say Eittlandic is still going strong and does not face any risk of disappearing anytime soon, although we might be at the start of the decline of the historical dialects of Eittland in favor of Standard Eittlandic.

In this document, we will mostly address Standard Eittlandic, although some dialectal variation will be mentioned.

Name of the Country

The root of the name of “Eittland” is the accusative of einn (Old Norse one, alone) and land (Old Norse country, land. This is due to how remote it seemed to the people who discovered, before Iceland and Greenland were known. Hence, a possible translation of “Eittland” can be Lonely Land. The term “Eittlandic” is relatively transparent considering the term “Icelandic” for “Iceland” and “Greenlandic” for “Greenland”.

History

Early Eittlandic History (7th-12th centuries)

According to historical records, Eittland was first found in 763 by Norwegian explorers. Its first settlement appeared in 782 on its eastern shores with hopes of finding new farmland. The population grew rapidly after the discovery of the southern shores, and in 915 Eittland became self-governing with Ásmundr Úlfsonn declared the first Eittlandic king. However, in order to avoid any unnecessary conflicts, the new king swore allegiance to the Norwegian king Harald I Halfdansson. Eittland thus became a vassal state to the Norwegian crown while retaining autonomy from it, which was granted due to the distance between the two countries.

Shortly after however, the beginning of the christianisation of the nordic countries and especially of Norway created a new immigration boost in Eittland with norsemen seeking a pagan land untouched by christian faith. In 935, a year after Haakon I Haraldsson became king of Norway and began trying to introduce Christianity to its people, the newly crowned king Áleifr I Ásmundson of Eittland adopted a new law forbidding the Christian faith to be imported, promoted, and practiced in Eittland. This decision forever weakened the alliance between the two countries and detariorated their relationship.

As more and more people in Eittland were moving to its western part due to larger opportunities with its farmlands, king Áleifr I chose in 936 to move the capital of Eittland from Hylfjaltr to Đeberget and split in half the country. He appointed his brother Steingrímr, later known as Steingrímr I Áleifsbróðr, as his co-ruler and gave him authority over Eastern Eittland while he kept ruling himself over Western Eittland. This choice is due to the difficulty of going from one side of the island to the other by land — lava flows often forcefully close and destroy paths joining the two parts together. This gave birth to the two states of the Kingdom of Đeberget (also called the Western Eittlandic Kingdom) and the Kingdom of Hylfjaltr (also called the Eastern Eittlandic Kingdom). More on that in §#Eittland-Political-Organization-z5v4e9p0jaj0.

Crusades and Independence (13th century - 1407)

As soon as the 13th century, and through the 14th century, the Teutonic Order and the Livonian Order, backed by the Holy Roman Empire, proposed crusades against Eittland to get rid of its norse faith. However, these never came to be due to the distance between Eittland and mainland Europe, despite the papal authorisations in 1228, 1257, 1289, 1325, and 1367.

In 1397, the creation of the Kalmar Union kicked a new crusade, this time backed by the Union itself as well as the Teutonic Order — Eric of Pomerania aimed to unify his country both religiously by getting rid of the norse faith in Eittland and politically by getting rid of its established monarchy. A contingent sailed to Eittland to submit the island, however they were met with fierce resistance by the locals on arrival. Estimates show that while some 2.400 Eittlandic people died during this first invasion, most of the 3.000 men sent were either killed or taken prisoners.

In 1398, a new contingent of 12.000 men landed in Eittland. This time, a much more prepared army of 14.000 men faced them on a battlefield east of the eastern capital of Hyfjaltr. This resulted in an Eittlandic victory, however the Monarch of Hylfjaltr Eiríkr IV Ásgeirsbróðr lost his life during the battle. Coincidentally, the High King Ásgeirr I Biœrgson died of unknown causes around the same time. Historians still debate whether it is due to the ongoing conflict, and if it is by who. Theories range from poisoning by spies from the Kalmar Union, to assassination by the next rulers, to a much more simple, unknown health condition which coincided with the ongoing events.

During the same year, the Althing elected Arvid I Geirson as the new High King who nominated his brother Havardr I Arvidbróðr as the Monarch of Hylfjaltr. While the previous monarchs took a more defensive approach, they chose to become much more aggressive, striving for independence. After demands were sent to the Kalmar Union, Eittland began a series of raids on its territories, ranging from Iceland to the Faroese Islands to even two raids in Norway and Denmark. These raids only aimed trade and military ships but severely handicaped the Union’s marine.

On September 17th, 1400 High King Arvid Geirson and King Erik met in Reykjavik to sign the Treaty of Reykjavik, during which the Kalmar Union recognized the independence of Eittland and renounced its claims to the island. Both parties agreed to end the hostilities towards one another.

While the Union no longer launched any crusades against Eittland, the Teutonic Order attempted to land again in 1407 with 4.000 men. Although the Kingdom of Hylfjaltr took a devastating blow during the initial days of the crusade, loosing well over 6.000 men, the invaders were ultimately defeated thanks to reinforcement from the Kingdom of Ðeberget. This marked the end of crusades in Eittland.

Political Organization

Kingdoms and Monarchy

While Eittland is a single country, it is host to two kingdoms: the Kingdom of Đeberget in the western part of the country, and the Kingdom of Hylfjaltr in its eastern part. This is due to a separation of the country in two halves during the reign of Eittlands second king Áleifr I when he realized the difficulties he and the following monarchs of the island would face trying to rule the country alone while the latter is almost always split in two by active volcanoes. Thus, while the two kingdoms operate very independently from each other — each have their own policies on economics, education, industry, and so on — they also operate in cooperation as the Eittlandic High Kingdom with the king of Đeberget at its head when it comes to common policies, such as military decision and internrational affairs.

This means that while both governments are independent from each other and are legally equals to each other, the western monarch is the one with the authority to decide on national actions after negotiations between them and the eastern monarch. This is reflected by the throne rooms found in official buildings such as the royal palaces where three thrones can be found: a central, very large throne surrounded by two other identical thrones, the right one for the monarch of Hylfjaltr and the left one for the king of Đeberget. Most of the time, both monarchs sit on their side throne, including when they meet each other as the monarchs of Hylfjaltr and Đeberget. However, when the monarch of Đeberget is meant to act as the High Monarch of Eittland, they step up to the central throne and then represent the country as a whole.

At the end of the reign of the High King, either through abdication or their death, his successor is enthroned within a month. Then, within a year, the new High King has to appoint a new monarch for Hylfjaltr. Traditionally, the new co-ruler is a brother of the current High Monarch, however history showed it could be sometimes an uncle, a son, a sister or even sometimes a daughter. When the eastern monarch either abdicates or dies, the High Monarch has a month to designate a new one.

Up until the 14th century, the monarch of Hylfjaltr was rarely the successor of the High Monarch. However, High King Ólafr I changed this tradition and created a new one. He named his brother and co-ruler King of Eittland and his son Prince of Eittland. From here on, the King (or occasionally the Queen) of Eastern Eittland was meant to become the new High Monarch of Eittland and make the Prince (or occasional Princess) the ruler of Hylfjaltr. Then, once the reign of the King ends, the Prince becomes the new High King and nominates a new King and a new Prince. This was done to ensure the upcoming High Monarch would be prepared in ruling the whole country by first ruling the state. If anything were to happen to the Prince or Princess of Eittland while the King or Queen of Hylfjaltr is on the throne, they would have to nominate a new heir among the other possible heirs possible for the late High Monarch.

When the High Monarchs steps up to the central throne, they may designate someone to fill in the role of the monarch of Đeberget for the time being. They can also authorize the monarch of Hylfjaltr to do so in case they are unavailable and someone need to represent the country in front of foreign representatives. The last example was during the two last years of Eríkr IX’s reign from 1987 to 1989 when he could not act as High King due to his illness. While he did not abdicate, he authorized king Harald III to act as High King while he appointed his daughter and present-day High Queen Njall III as the acting monarch of Đeberget.

Regions and Jarldoms

While each kingdom is ruled by a monarch and the country is ruled by the High Monarch, the kingdoms are divided into several kinds of subdivisions. The most common one is the jarldom, historically ruled by and still represented by a jarl during ceremonies. “Jarl” translates as “Earl” in English, and they were the nobles in charge of managing parts of the land in the name of the ruler.

Some parts of the land are directly under the control of the crown, such as the districts of Đeberget and Hylfjaltr, which the ruler ruled without intermediaries. They are the private possessions of the family of the rulers.

On top of this the center of the island is divided in territories, one administered by the government of Đeberget and two by the government of Hylfjaltr. These territories are supposedly not inhabited by anyone and are currently natural parks. This is mostly where you can find the mountains and volcanoes of Eittland as well as its cold deserts.

Due to the Last Royal Decree of 1826, jarls no longer rule their jarldom themselves anymore. Instead, a local elected government takes care of this role now.

Governments

Monarchy and Things

The first form of government created in Eittland revolved around Things (þing in Eittlandic), assemblies of varying size occasionally created at various levels of the state to decide on important matters, with the Althing being the highest Thing to exist in Eittland. The Things allow at first any adult man to participate, but as the population grew some restrictions were put in place in order to limit the amount of participants. Only one man could represent a household starting from 982. Then, starting from 998, only jarls were allowed to the ruler’s Thing, and only ten jarls from each kingdom, elected among all the jarls from the same kingdom, would be allowed to attend the High Monarch’s Thing. These jarls would then act as representatives of the kingdom to the High King and his counsellors.

In 1278, the first formal ministry (or department) was created in the Ðeberget Kingdom, called a Ráðuneyt (litt. “fellowship of counsellors”) with a Ráðunautr at its head, to aid the King Hallþórr V Gunhildson’s in administering agriculture. The Hylfjaltr Kingdom soon followed, creating its own in 1283 by order of Eyvindor III Steingrímson. From then, ráðuneyts were created as needed with a growing number.

Constitutional Monarchy

In 1826, fearing the revolutionary climate in mainland Europe, Ólafr V passed the appropriately named “Last Royal Decree” in 1826. This act put in place a new form of government based on the British monarchy.

The king transfers all the royal power from the rulers of Đeberget and Hylfjaltr to the House of the People and the House of the Land (the equivalent of the lower and upper Houses respectively). The House of the People is composed of men elected during general elections every eight years. It was decided for each jarldom and district, one representative would be elected plus another one for each percentage of the population of the kingdom the jarldom represents.

A similar system was created for jarldoms in order to replace jarls with locally elected governments, as well as the organisation of municipalities.

At first only male land owner of the Nordic Faith could vote and could be elected. In 1886, all men of the Nordic Faith got the right to vote and be elected in the general elections. In 1902, women gained the right to vote and they gained the right to be elected in 1915. The law that allowed women to vote also made the authorities stop enforcing the restriction on the faith of the participants — while the original texts of 1826 and 1886 were clear on the fact only men of the Nordic Faith were allowed to vote and be elected, women had no such restriction making it unclear if it only applied to women or if this restriction was revoked for everyone. Organizers of the next elections in 1914 chose not to enforce this religious restriction and ever since then. In 1998, Queen Siv I exceptionally used her powers of High Queen to pass a law to clarify this issue and formally make Eittland a non-religious country. This also removed the long unenforced ban on other religions in Eittland.

Note that while the rulers of Đeberget and Hylfjaltr have lost all their power with the “Last Royal Decree”, the High Monarch remained unaffected by the text though they act and are expected to act as if it were the case. To replace them, the eastern and western governments elect a single national representative meant to act as the head of both states instead of the High Monarch who now holds only a ceremonial position. However, it happens from time to time the High Monarch passes a law, although they only write down in the law already well established traditions, such as the ban on the religious restrictions for voters which had not been enforced for almost a century by that point.

Today, Ráðuneyts still exist, but their head is no longer designated by the monarch but by the head of the House of the People. Here is the list of Ministries that exist in Eittland in 2022:

- Bærráðuneyt

- Agriculture Ministry

- Dæmaráðuneyt

- Justice Ministry

- Erlendslandsráðuneyt

- Foreign Affair Ministry

- Fræðiráðuneyt

- Education Ministry

- Heilsráðuneyt

- Health Ministry

- Konungdómráðuneyt

- Kingdom’s Ministry (State Affairs)

- Náttúrráðuneyt

- Nature Ministry (including ecology)

- Rógráðuneyt

- War Ministry

- Teknikráðuneyt

- Technology Ministry

- Kaupráðuneyt

- Economy Ministry

- Vinnaráðuneyt

- Employment Ministry

With the separation of the State with its religious departments following the law of 1998, the Heiðniráðuneyt (the Heathendom Department) became an entity separate from the Government. Its Ráðunautr used to be exceptionally appointed by the House of the Land, unlike the rest of Ráðunautrs.

Structural Overview

Typological Outline of the Eittlandic Language

Over the last centuries, Eittlandic evolved to become a language leaning more and more towards an analytic language, losing its fusional aspect Old Eittlandic once had. It grammar now greatly relies on its syntax as well as on grammatical particules rather than on its morphology. Let’s take the following sentence as an example.

-

barn fisk etar / a child is eating a fish

barn fisk et-ar child.NOM fish.ACC eat-3sg

In this sentence, the word order helps us understand the child is the subject of the sentence while its subject is fisk, although we have no information on their number; the sentence could also very well mean children are eating fishes. Unlike in Old Eittlandic where we could have the following sentences.

-

barn fiska etar

barn fisk-a et-ar child.NOM fish-pl.ACC eat-3sg -

fiska barn etar

fisk-a barn et-ar fish-pl.ACC child.NOM eat-3sg

Both have the same meaning as the Eittlandic sentence. However, the near-complete (or even complete in Standard Eittlandic) loss of case marking makes the sentence fisk barn etar much more gruesome.

-

fisk barn etar / a fish is eating a child

fisk barn et-ar fish.NOM barn.ACC eat-3sg

Eittlandic is now a SOV language with a much stricter word order than it used to be. This is an important change since Old Eittlandic which main word order was VSO instead. For instance, here is the same sentence in Old Eittlandic and in Standard Eittlandic, meaning he carried him to some lake.

- Old Eittlandic

-

Han bar hann til vatns nákkurs

han bar han-n til vatn-s nákkur-s he.NOM carry.3sg.pret 3sg.m-ACC to lake-DAT some-DAT - Standard Eittlandic

-

Han til vatn nákkur hann bar

han til vatn nákkur hann bar 3sg.m.NOM to lake some he.ACC carry.3sg.pret

Eittlandic still retains VSO word order in its relative and interrogative clauses, as shown below.

-

Han mér talð þat kom han hér í gær / he told me he came here yesterday

han mér tal-ð þat kom han hér í gær 3sg.m.NOM 1sg.DAT tell-3sg.PRET that come.3sg.PRET 3sg.m.NOM here yesterday

Loss of case marking also affected adjectives which share most of their declensions with nouns. The parts where Eittlandic retains its fusional aspect is with verbs, where loss of its words’ final vowel had much less impact, as we could see in barn fisk etar. In this case, etar is the third person singular declension of the verb et, a weak verb.

Phonetic Inventory and Translitteration

Evolution from Early Old Norse to Eittlandic

Eittlandic evolved early on from Early Old Norse, and as such some vowels it evolved from are different than the Old Norse vowels and consonants some other Nordic languages evolved from. In this chapter, we will see the main list of attested phonetic evolution Eittlandic lived through.

The history of Eittlandic goes from the late 8th century until modern-day Eittlandic. Its history is divided as shown on table table:history-eittlandic-language. It is not an exact science though as changes happened progressively through the country. Changes were also progressive, meaning the dates chosen to go from one language to the other are relatively arbitrary. In evolution examples, it will be indicated whether the Eittlandic pronunciation is specific to a certain time area (with Early Middle Eittlandic, Late Old Eittlandic, etc…) but if it only specifies Eittlandic it means no significant changes in pronunciation occurred since the phonetic rule shown. Meaning is also shown between parenthesis. In case of semantic shift, its new meaning in Eittlandic is shown — the same goes for the word’s spelling.

| Period | Language |

|---|---|

| 8th century - 12th century | Old Eittlandic |

| 13th century - 16th century | Middle Eittlandic |

| 17th century - today | Modern Eittlandic |

It is generally considered the gj-shift of the 13th century is the evolution that marks the change from Old Eittlandic to Middle Eittlandic while the great vowel shift marks the change from Middle Eittlandic to Modern Eittlandic between the 16th and the 17th century.

hʷ > ʍ

One of the first evolution of the Eittlandic was the evolution of the (written <hv>). It differs from other nordic languages which evolved their , like in Icelandic or in Norwegian. However, this evolution is cause to debate, mainly due to the original phoneme which could be inherited from Proto-Norse instead.

- Example

- Early Old Norse or Late Proto-Norse hvat (what)

C / #h_ > C[-voice]

When preceded by a , word-initial consonants such as <l>, <r>, <n> would lose their voicing and become voiceless consonants. Note <hj> went to .

- Example

-

- Early Old Norse hlóð (hearth) > Old Eittlandic hlóð

- Early Old-Norse hneisa (shame, disgrace) > Early Old Eittlandic

- Early Old Norse hrifs (robbery)

- Early Old Norse hjól (wheel)

g / {#,V}_{V,#} > ɣ

In word-initial position and followed by a vowel or when between vowels, Early Old Norse .

- Example

- Early Old Norse gegn (against, right opposite) > Old Eittlandic

V / _# > ∅ ! j _

When finishing a word, short unaccented vowels disappeared. Historically, they first went through a weakening transforming them into a , but they eventually disappeared before long vowels got affected by the first part of the rule. However, it did not apply to final vowels following a <j>.

- Example

- Old Norse heilsa (health) > Late Old Eittlandic heils .

Reflecting this change, the last vowel got lost in the Eittlandic orthography. However, this rule did not get applied consistently with a good deal of people that kept them well until the Great Vowel Shift.

V / j_# > ə

While the final short vowel of words did not disappear when preceded by a <j>, they still weakened to a schwa.

- Example

- Old Norse sitja (to sit) > Old Eittlandic

Vː / _# > ə

When at the end of a word, long unaccented vowels get weakened into a schwa.

- Example

- Old Norse erþó (as though) > Late Old Eittlandic .

Notice how in the modern orthography the <ó> didn’t get lost, unlike with the previous rule. Unlike the schwa from the previous rule, the current schwa still bears the long vowel feature although it is not pronounced anymore by that point, influencing the rule described in §#Structural-Overview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-ə-C-voice-ysvblnk08bj0.

ɣ / {#,V}_ > j

During the 13th century, continued palatalization of the letter <g> when beginning or preceding a vowel transformed it from in Proto-Norse to in Early Modern Eittlandic.

- Example

- Old Norse gauð (a barking) > Early Middle Eittlandic gauð (a barking, a quarrel) .

This is the first rule of the g/j-shift along with the three next rules, marking the passage from Old Eittlandic to Middle Eittlandic.

gl > gʲ

The exception to the above rule is the <g> remains a hard when followed by an <l> in which case .

- Example

- Old Norse óglaðr (sad, moody) > Early Middle Eittlandic óglaðr (very sad, miserable)

d g n s t / _j > C[+palat]

Another exception to the rule in §#Structural-Overview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-t-C-ʔ-x7lfpz90uaj0 is the <g> remains a hard , in which case , also get palatalized, merging with the following . In the end, we have the conversion table given by the table cons:palatalization.

| Early Old Norse | Eittlandic |

|---|---|

Note this is also applicable to devoiced consonants from the rule described in §#Structural-Overview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-C-h-voice-o4r8mvg08bj0.

- Example

-

- Early Old Norse djúp (deep) > Middle Eittlandic djúp (deep, profound)

- Early Old Norse gjøf (gift) > Early Middle Eittlandic

- Early Old Norse snjór (snow) > Middle Eittlandic

- Early Old Norse hnjósa (to sneeze)

- Early Old Norse sjá (to see)

- Early Old Norse skilja (to understand, to distinguish)

- Old Eittlandic sitja (to sit)

j > jə / _#

With the appearance of word-final appeared due to the phonological rule forbidding word-final consonant clusters to end with a .

- Example

-

- Early Old Norse berg (rock, boulder) > Middle Eittlandic berg

u / V_ > ʊ

When following another vowel, .

- Example

- Old Norse kaup (bargain) > Early Middle Eittlandic

{s,z} / _C[+plos] > ʃ

If precede a plosive consonant, they become palatalized into a — the distinction between <s> and <z> is lost.

- Example

-

- Old Norse fiskr (fish)

- Early Old Norse vizka (wisdom) > Middle Eittlandic viska

Note that in the Modern Eittlandic orthography, the <z> is replaced with an <s>.

f / {V,C[+voice]}_ {V,C[+voice],#} > v

When a <f> is either surrounded by voice phonemes or is preceded by a voiced phoneme and ends a word, it gets voiced into a .

- Example

- Old Norse úlf (wolf) .

l / _j > ʎ

When followed by a <j>, any <l> becomes a , merging with the following <j>.

- Example

- Early Middle Eittlandic skilja (to understand, to distinguish)

ə[-long] / C_# > ∅

As described in the rule §#Structural-Overview-Phonetic-Inventory-and-Translitteration-Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-Vː-ə-9w7dgz60uaj0, the schwa resulting from it kept its long vowel feature although it wasn’t pronounced anymore. This resulted in the current rule making all schwas resulting from short vowels at the end of words to disappear when following a voiced consonant. This basically boils down to any former short vowel following a <j> in word-final position.

- Example

- Middle Eittlandic (to understand, to distinguish)

ɑʊ > oː

Sometime in the 15th century, any occurence of <au>, pronounced by then .

- Example

- Early Middle Eittlandic kaup (bargain) > Late Middle Eittlandic kaup (commerce) {{{koːp}}}

C[+long +plos -voice] > C[+fric] ! / _C > C[+long +plos] > C[-long]

Unless followed by another consonant, any unvoiced long plosive consonant becomes a short affricate while other long plosives simply become shorter.

- Example

-

- Old Norse edda (great grandmother) > Late Middle Eittlandic edda (great grandmother, femalle ancestor)

- Old Norse Eittland

- Old Norse uppá (upon)

r > ʁ (Eastern Eittlandic)

From the beginning of the 16th century, the Eastern Eittlandic began morphing into an in all contexts except in word-final <-r>, remanants of Old Norse’s nominative <-R>. This is typical in the Eastern region of Eittland and it can be even heard in some dialects of Southern Eittlandic.

- Example

-

- Old Norse dratta (to trail or walk like a cow) > Eastern Modern Eittlandic dratt (act mindlessly)

- Early Old Norse fjárdráttr ((unfairly) making money) > Eastern Modern Eittlandic fjárdráttr (to scam)

Great Vowel Shift

The great vowel shift happened during the 16th and 17th century during which long vowels underwent a length loss, transforming them into different short vowels. Only three rules governed this shift:

- V[+high +long] > V[-high -long]

- V[+tense +long] > V[-tense -long]

- V[-tense +long] > V[-long -low]

Hence, the vowels evolved as shown in table vow:eittland:evolution.

| Orthography | Old Eittlandic vowel | Modern Eittlandic Vowel |

|---|---|---|

| á | ||

| é | ||

| í | ||

| ó | ||

| œ (ǿ) | ||

| ú | ||

| ý |

As you can see, some overlap is possible from Old Norse vowels and Modern Eittlandic vowels. For instance, Eittlanders will read <e> and <í> both as an .

- Examples

-

- Middle Eittlandic sjá (to see)

- Old Norse fé (cattle)

- Late Proto-Norse hví (why)

- Old Norse bók (beech, book) > Modern Eittlandic (book)

- Early Old Norse œgir (frightener, terrifier) > Modern Eittlandic Œgir (a kind of mythical beast)

- Middle Eittlandic úlv (wolf)

Diphthongs also evolved following these rules:

V / _N > Ṽ[-tense] ! V[+high] (Southern Eittlandic)

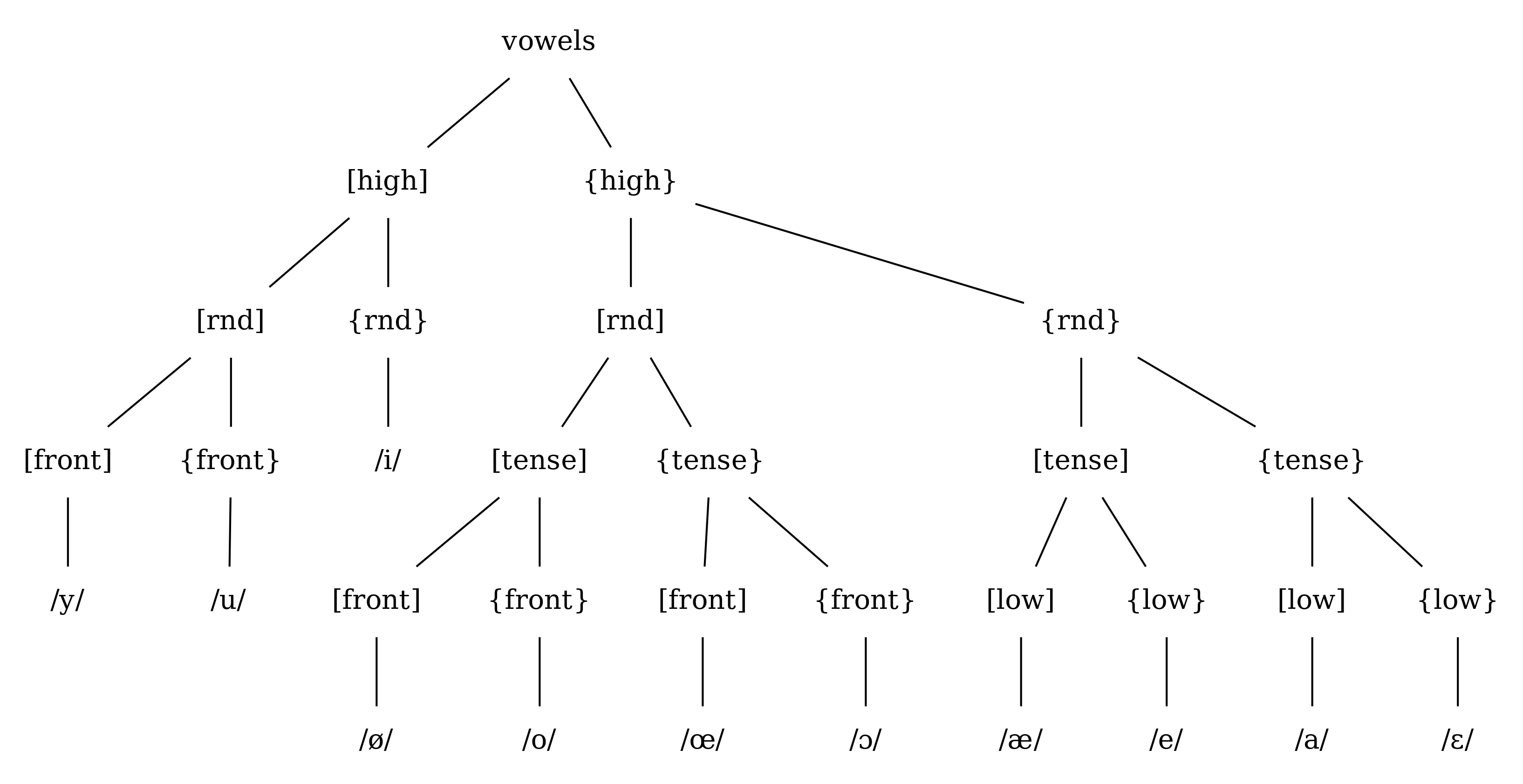

When preceding a nasal, any vowel that is not high as determined by the figure tree:vowels gets nasalized when preceding a nasal consonant and loses its tenseness if it has any. Hence, the pronunciation of the <a> in Eittland is becomes run (letter, character, rune) without any nasalization.

Note this evolution is mostly proeminent in the southern regions of Eittland and the city of Hundraðskip. It is less often documented in Eastern Eittland and almost undocumented in Western Eittland. It is more often documented in casual conversation buch rarer in formal conversation, especially when the majority of the speakers in a group are not southerners.

t / _C > ʔ ! _ʃ

When a precedes another consonant, it becomes a glottal stop.

- Example

- Early Modern Eittlandic Eittland > Modern Eittlandic

VU > ə ! diphthongs (Western Eittlandic)

A recent evolution in Western Eittland is weakening any unstressed vowel that is not a diphthong to a schwa. It is only documented in casual speech but almost never in formal speech.

- Example

-

- Standard Eittlandic ádreif (spray) > Western Casual Eittlandic

- Standard Eittlandic einlægr (sincere) > Western Casual Eittlandic

Vowel Inventory

Modern Standard Eittlandic has a total of ten simple vowels and three diphthongs. Unlike its ancestor language, Old Norse, it does not bear any distinction in vowel length anymore since the great vowel shift (see §#Great-Vowel-Shift-7spk7j70uaj0). The table tab:vow:ipa lists the Eittlandic simple vowels while the table tab:vow:dipththongs lists the Eittlandic diphthongs.

| / | < | |

|---|---|---|

| front | back | |

| close | i y | u |

| close-mid | e ø | o |

| open-mid | ɛ œ | ɔ |

| open | ɑ |

| diphthong | phonetics |

|---|---|

| ei | |

| au | |

| ey |

(conlanging-list-to-graphviz vowels)graph{graph[dpi=300,bgcolor="transparent"];node[shape=plaintext];"vowels-0jbs0vhl86d2"[label="vowels"];"+high-0jbs0vhl86db"[label="+high"];"vowels-0jbs0vhl86d2"--"+high-0jbs0vhl86db";"+round-0jbs0vhl86de"[label="+round"];"+high-0jbs0vhl86db"--"+round-0jbs0vhl86de";"+front-0jbs0vhl86dg"[label="+front"];"+round-0jbs0vhl86de"--"+front-0jbs0vhl86dg";"/y/-0jbs0vhl86dj"[label="/y/"];"+front-0jbs0vhl86dg"--"/y/-0jbs0vhl86dj";"-front-0jbs0vhl86do"[label="-front"];"+round-0jbs0vhl86de"--"-front-0jbs0vhl86do";"/u/-0jbs0vhl86dr"[label="/u/"];"-front-0jbs0vhl86do"--"/u/-0jbs0vhl86dr";"-round-0jbs0vhl86e3"[label="-round"];"+high-0jbs0vhl86db"--"-round-0jbs0vhl86e3";"/i/-0jbs0vhl86e6"[label="/i/"];"-round-0jbs0vhl86e3"--"/i/-0jbs0vhl86e6";"-high-0jbs0vhl86ek"[label="-high"];"vowels-0jbs0vhl86d2"--"-high-0jbs0vhl86ek";"+round-0jbs0vhl86en"[label="+round"];"-high-0jbs0vhl86ek"--"+round-0jbs0vhl86en";"+tense-0jbs0vhl86ep"[label="+tense"];"+round-0jbs0vhl86en"--"+tense-0jbs0vhl86ep";"+front-0jbs0vhl86es"[label="+front"];"+tense-0jbs0vhl86ep"--"+front-0jbs0vhl86es";"/ø/-0jbs0vhl86ev"[label="/ø/"];"+front-0jbs0vhl86es"--"/ø/-0jbs0vhl86ev";"-front-0jbs0vhl86f2"[label="-front"];"+tense-0jbs0vhl86ep"--"-front-0jbs0vhl86f2";"/o/-0jbs0vhl86f4"[label="/o/"];"-front-0jbs0vhl86f2"--"/o/-0jbs0vhl86f4";"-tense-0jbs0vhl86ff"[label="-tense"];"+round-0jbs0vhl86en"--"-tense-0jbs0vhl86ff";"+low-0jbs0vhl86fh"[label="+low"];"-tense-0jbs0vhl86ff"--"+low-0jbs0vhl86fh";"/œ/-0jbs0vhl86fk"[label="/œ/"];"+low-0jbs0vhl86fh"--"/œ/-0jbs0vhl86fk";"-low-0jbs0vhl86fp"[label="-low"];"-tense-0jbs0vhl86ff"--"-low-0jbs0vhl86fp";"/ɔ/-0jbs0vhl86fs"[label="/ɔ/"];"-low-0jbs0vhl86fp"--"/ɔ/-0jbs0vhl86fs";"-round-0jbs0vhl86gm"[label="-round"];"-high-0jbs0vhl86ek"--"-round-0jbs0vhl86gm";"+tense-0jbs0vhl86gp"[label="+tense"];"-round-0jbs0vhl86gm"--"+tense-0jbs0vhl86gp";"/e/-0jbs0vhl86gr"[label="/e/"];"+tense-0jbs0vhl86gp"--"/e/-0jbs0vhl86gr";"-tense-0jbs0vhl86gw"[label="-tense"];"-round-0jbs0vhl86gm"--"-tense-0jbs0vhl86gw";"+low-0jbs0vhl86gz"[label="+low"];"-tense-0jbs0vhl86gw"--"+low-0jbs0vhl86gz";"/ɑ/-0jbs0vhl86h1"[label="/ɑ/"];"+low-0jbs0vhl86gz"--"/ɑ/-0jbs0vhl86h1";"-low-0jbs0vhl86h6"[label="-low"];"-tense-0jbs0vhl86gw"--"-low-0jbs0vhl86h6";"/ɛ/-0jbs0vhl86h9"[label="/ɛ/"];"-low-0jbs0vhl86h6"--"/ɛ/-0jbs0vhl86h9";}

- a

- á

- æ

- e

- é

- i

- í

- o

- ó

- u

- ú

- y

- ý

Consonant Inventory

Pitch and Stress

Regional accents

Eittlandic is a language in which three distinct main dialects exist with their own accent. These three main dialects are Eastern Eittlandic spoken in the majority Kingdom of Hylfjaltr, Western Eittlandic spoken in the majority of the Kingdom of Ðeberget, and Southern Eittlandic spoken on the southern parts of the island, regardess of the legal kingdom (see the map shown in §#Eittland-Culture-q6uf2gs0uaj0. Three main elements of their respective accent were presented above in §§#Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-r-ʁ-Eastern-Eittlandic-b20i1pm0bbj0, #Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-V-N-Ṽ-V-high-ulb1ey80uaj0, and #Evolution-from-Early-Old-Norse-to-Eittlandic-V-U-ə-diphthongs-fjh0pnr0uaj0.

Some regional variation can be also found in these dialects, although less significant and less consistantly than the changes mentioned above. As such, we can find in some rural parts of the Eastern Eittlandic dialect area high vowels slightly more open than their equivalent in Standard Eittlandic, as shown in table vow:accent:east

| Rural Eastern Eittlandic | Standard Eittlandic |

|---|---|

On the other hand, Southern Eittlandic tends to front its into otherwise.

Structure of a Nominal Group

Grammatical Case

Cases in Modern Eittlandic

Although seldom visible, as described in §#Structural-Overview-Structure-of-a-Nominal-Group-Grammatical-Case-Case-Marking-c6jb9o11mfj0, cases still remain part of the Eittlandic grammar, expressed through its syntax rather than explicit marking on its nouns and adjectives. Four different grammatical cases exist in this language: the nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative case.

- The nominative case represents the subject of a sentence, that is, the subject of intransitive clauses and the agent of transitive clauses. As we’ll see below, it is morphologically marked only in dialects other than Standard Eittlandic, and only if the word is a strong masculine word.

- On the other hand accusative, like Old Norse, usually marks the object of a verb, but it can also express time-related ideas such as a duration in time, or after some prepositions. It is also the default case when a noun has no clear status in a clause, and it can as such serve as a vocative.

- Dative usually marks indirect objects of verbs in Old Norse, though it can also often mark direct objects depending on the verb used.

Case Marking

Although present in Early Old Norse, the use of grammatical cases has been on the decline since the Great Vowel Shift (see §#Great-Vowel-Shift-7spk7j70uaj0). Due to the general loss of word-final short vowels and to regularization of its nouns, Eittlandic lost almost all of weak nouns’ inflexions and a good amount in its strong nouns’ inflexions. On top of this, the root of most nouns got regularized, getting rid of former umlauts. Hence, while in Old Norse one might find the table tbl:old-norse-noun-inflexions presented in Cleasby and Vigfusson (1874), Modern Eittlandic is simplified to the table tbl:eittlandic-example-noun-inflexions.

| / | <r> | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Masculine | Strong Feminine | Strong Neuter | Weak Masculine | ||

| Sing. Nom. | heim-r | tíð | skip | tím-i | |

| Acc. | heim | tíð | skip | tím-a | |

| Gen. | heim-s | tíð-ar | skip-s | tím-a | |

| Dat. | heim-i | tíð | skip-i | tím-a | |

| Plur. Nom. | heim-ar | tíð-ir | skip | tím-ar | |

| Acc. | heim-a | tíð-ir | skip | tím-a | |

| Gen. | heim-a | tíð-a | skip-a | tím-a | |

| Dat. | heim-um | tíð-um | skip-um | tím-um |

| / | <r> | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Masculine | Strong Feminine | Strong Neuter | Weak Nouns | ||

| Sing. Nom. | heim-r | tíð | skip | tím | |

| Acc. | heim | tíð | skip | tím | |

| Gen. | heim-s | tíð-s | skip-s | tím-s | |

| Dat. | heim | tíð | skip | tím | |

| Plur. Nom. | heim-r | tíð-r | skip | tím-r | |

| Acc. | heim | tíð-r | skip | tím | |

| Gen. | heim | tíð | skip | tím | |

| Dat. | heim-um | tíð-um | skip-um | tím-um |

As you can see, grammatica cases disappeared in singular nominative (except for strong mascuine nouns), accusative, and dative as well as in plural accusative and genitive. The only markers remaining are for singular genitive, plural nominative and dative as well as singular nominative for strong masculine words. Note however that strong nouns are no longer productive and get slowly replaced with weak nouns.

Note also how the last column in table tbl:eittlandic-example-noun-inflexions is not Weak masculine as in table tbl:old-norse-noun-inflexions but Weak Nouns. This is due to weak nouns’ inflexions merging together, yet again due to the final vowel loss and regularization of these inflexions. Only strong nouns remain separated, although by minor differences. All nouns get a case marker -s for singular genitive, -r for plural nominative, and -um for plural dative. However, strong masculine nouns also get an -r on singular nominative nouns, strong feminine nouns get an -r on plural accusative nouns, and strong neuter nouns lose their -r on plural nominative nouns.

Note also the -r suffix becomes an -n when added to a word ending with an <n>. For instance, the word brún (eyebrow) becomes brúnn in its plural nominative form instead of brúnr.

Case markers are no longer productive and only server for redundancy with Modern Eittlandic’s syntax. The Royal Academy for Literature, which authored Standard Eittlandic, even recommends not using them to simplify the language, as they deemed them no longer necessary for understanding Eittlandic. While this recommendation is widely adopted by Standard Eittlandic speakers, singular genitive -s still remains used even in this dialect.

Dictionary

A

Á

Æ

B

- bók

-

- book

C

D

- djúp

-

adj.

- deep

- profound (figuratively)

- djúpligr

-

adv.

- deeply

Đ

E

- edda

-

- great grandmother

- female ancestor, beyond the grandmother

- Eittland

-

- (n) High Kingdom of Eittland, island of Eittland

É

F

- fé

-

- wealth

- fisk

-

- fish

G

- gauð

-

- a barking

- a quarrel

- gegn

-

adv.

- against, opposing

- gjøf

-

- gift, present

H

- heilsa

-

- health

- hjól

-

- wheel

- hlóð

-

- hearth

- living room

- hneisa

-

- shame, disgrace

- social isolation

- hneising

-

- hermit

- (modern) shut-in, hikikomori

- hnjósa

-

- to sneeze

- hrifs

-

- assault, mugging

- hvat

-

adv.

- what

- hví

-

adv.

- why

I

Í

J

K

- kaup

-

- commerce

- bargain, barter

L

M

N

- noregsúlf

-

- wolf, litt. Norway’s wolf. Wolf do not naturally live in Eittland and their only relatives introduced to the island were dogs and wolf-dogs which inherited the simpler úlfr term. Noun composed by Old Norse noregs (genitive of Noregr, Norway) and úlfr.

O

Ó

- óglaðr

-

adj.

- very sad, depressed, miserable

Ø

Œ

- Œgir

-

- A mythical beast residing in the forests of the western Eittlandic fjords.

P

Q

R

S

- sitja

-

- to sit

- to represent (politics)

- sjá

-

- to see

- to understand

- skilja

-

- to differenciate

- to segregate, to separate

- to understand a difference

- snjór

-

- snow

T

Þ

U

- uppá

-

prep.

- upon

Ú

- úlf

-

- wolf-dog. See also noregsúlfr.

V

- veisheit

-

- knowledge or wisdom. From German Weisheit. See also vizka

- viska

-

- practical knowledge or wisdom, acquired from experience

See veisheit for a more general term for wisdow